🕵️Does censorship increase support for regimes? + My experience in 🇰🇵 North Korea and 🇨🇳China.

Governments that censor may gain support from citizens--but it's complicated.

A hand-painted propaganda mural in North Korea (photo taken during my visit in 2013)

It has recently been reported that several Chinese GPT LLM variants have large amounts of imperfect censorship. A Bloomberg reporter notes he could not even type in the name of China’s leader in Chinese (seemingly even if his query were written in a positive light). In honor of this occasion, today’s episode of The Studies Show is about censorship. We not only look at several academic studies on the topic, but also explore some of my firsthand experiences when living in China and visiting North Korea. Let’s dive in:

The Key Question: Why do so many people accept censorship?

In many countries censorship is pervasive. You can’t criticize the government, or you might get hauled off the jail (or worse). Yet many countries with heavy censorship not only have stable governments, but many people seem to support censorship policies (and not just because they are pretending).

Is it because people get desensitized? Or is it because the government censors so many topics that people relate censorship less to politics?

Yang (2022) studies censorship in China and persuasively argues it is probably both of the above.

“The central argument of this paper is that, when the targets of censorship include both political and non-political content, it normalizes the censorship apparatus and desensitizes citizens to censorship activities. As a result, backlash against both the censorship apparatus and the regime is less likely to happen.’

In the American imagination we often think that countries such as China only censor anti-government content. But lots of things are censored there, notably including pornography, information about wealth gaps, and some historical facts about Maoism. (Chinese media also memorably censored crowd photos of the World Cup while China was still locked down). As we will discuss later, I found both in living in Shanghai and visiting North Korea that this censorship was highly class dependent, with Chinese and North Korean elites, as well as foreigners in China, seemingly experiencing much less censorship than average people. It’s important to note that this is not a phenomenon limited to one or two countries. Another study (Esberg, 2020) found similar activities in Chile during the rule of Pinochet, who not only censored political topics, but also content the Catholic Church didn’t like.

Yang’s paper suggests that the widespread use of censorship contributes to its normalization. It reminds me as a kind of inverse of Steve Bannon’s famous quote that the way to beat the media is to ‘flood the zone with shit’.

How Yang (2022) Studies Censorship

Yang first verifies that large amounts of non-political content is censored by looking at around 15,000 censored WeChat posts. Only about 40% of posts in his sample are politically related. (WeChat, if you don’t know, is an ‘everything app’ of the kind Musk is trying to turn Twitter (X) into. It has messaging, payments, apps, food delivery, shopping, all in one app).

Next, he shows two groups of people WeChat posts, some of which note they were censored. In the first group, he shows political and non-political posts, but only displays censorship notices on the political content. (This is the control group). In the second group, he shows censorship notices on some political and some non-political content (this is the treatment group).

As you can see in this chart from his paper, Yang (2022) finds that users exposed to both political and nonpolitical censorship were much more likely to support the censorship apparatus and express satisfaction for the regime. They were also less likely to express a desire to participate in protests.

Yang notes:

“Combining the results from the survey experiment and the observational study, I show that large-scale censorship of non-political content exists in China and can significantly increase support for the regime.”

What is it like on the ground in countries with heavier levels of censorship than the United States? While I cannot definitively speak to the present moment, I did live in Shanghai for six months in 2012, and spent approximately six days in North Korea in 2013. This is hardly enough time to make a definitive conclusion,, but given the paucity of foreigners who even visit NK, I think it is worth sharing some observations in regards to censorship and Yang’s findings.

Takeaway #1: Censorship is class dependent

In North Korea, very few people are able to interact with foreigners. Walking on the street of Pyongyang, children looked at me—several wide-eyed—but then generally quickly pretended they did not see me. As a 6’3 male with long hair, I was almost certainly one of the tallest people they had ever seen, and perhaps the only man without a crew cut. This fact alone makes me feel better about my visit—that I could even exist showed locals that the world outside the country was very different than the world inside.

But the people who could talk to you—and this was only a handful, really—did know about the outside world. A tour guide told me that students at the foreign studies university are shown western films to help them learn English. And it goes without saying that NK is so different from America that even the most bland film would show a radically different world. Even for a remarkably closed off regime, the decisionmakers (and even people who interact with foreign tourists) simply cannot have the same level of censorship everyone else has.

In Shanghai (where I lived for six months in 2012), locals who spoke English often had VPNs or found ways to access the internet. I briefly dated a woman who was active on Twitter, even though English was her second language and Twitter was technically banned. You could download anything on the internet if you knew where to look, and it seemed to me like only the very most political movies were really suppressed. The reality was that most people could not speak English, so foreign movies and ideas were not that much of a threat if consumed in English. My recollection is that The Economist was available in foreign hotels, although I recall an article which had apparently gone too far was a blank page in one edition.

During those six months, I also stayed for one night in some sort of luxury foreign-brand hotel in a skyscraper in Shanghai. To my surprise, the internet worked uncensored just fine, although I am sure the government was checking which sites I visited. I didn’t search for porn or Tiananmen pictures though, so it is possible there were limits that I didn’t brush up against. It’s also possible that this was only doable in English, and that use of Chinese would have run up against censorship.

Takeaway #2: Degrees of Censorship Matter Greatly

The freest I have ever felt, in my entire life, by far, is when I entered China from North Korea. It was like a night and day experience. I could go where I wanted without being followed by a “tour guide.” I was in possession of my own passport. I could choose which restaurant to eat at. I could also connect to the internet, call my family in America whenever I wanted, send emails, etc. You have to go to North Korea to understand just how lucky most Chinese people must feel. Indeed many Chinese friends have compared North Korea to China during the cultural revolution. Chalk that up as one reason why many people will support their government. Things are genuinely much better now.

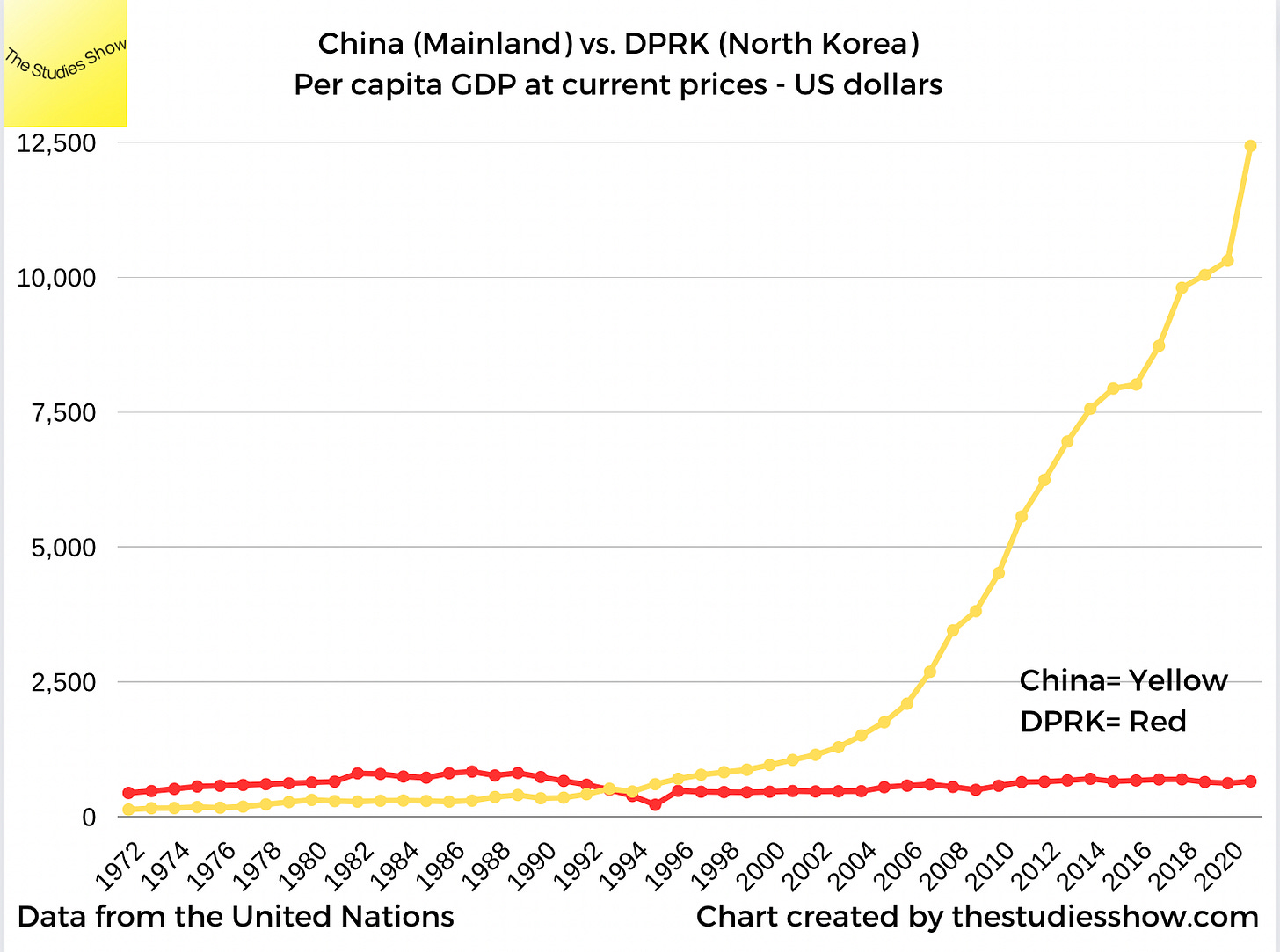

This chart I created using UN Economic Data shows the huge difference in economic growth between China and North Korea. Note that from 1972-to 1993 North Korea was apparently richer than China, a statistic which I find hard to believe having been to both places, but must speak to the absolute chaos of the Cultural Revolution. It presumably also speaks to the fact that China is much more open than North Korea.

“By joining the WTO, China is not simply agreeing to import more of our products, it is agreeing to import one of democracy’s most cherished values: economic freedom. When individuals have the power…to realize their dreams, they will demand a greater say.”

-Bill Clinton

Many people have (in many cases, rightly) criticized politicians like Bill Clinton for being too upbeat that China would liberalize. But at least based on my limited experience in China and NK, some of that liberalization did indeed occur, and does appear sticky. It is however, certainty the case, that it appears the odds of China becoming a western-style democracy soon are very slim. (I highly recommend Acemoglu and Robinson’s The Narrow Corridor).

Some foreigners lump China and North Korea together, but in reality there are huge differences between the two nations.

A Picture I Took In Kaesong, North Korea in 2013

One interesting divergence between the two countries seems to be around sexual attitudes. It is possible to hook up or have casual relationships in China, and openly discuss it to some degree, but this appears to be taboo in NK.

The only time one of my North Korean tour guides directly criticized China was in regard to dating, where the guide claimed that Chinese attitudes towards sex were too permissive. (The guide, as I recall, never said the word “sex” but it was clearly implied, as the discussion involved condoms and birth control.)

It was asserted that North Koreans preferred traditional matchmaking, without intercourse, and with serious discussions between the couple, and likely their families. In this case, the society was downright conservative, even though it is in theory

All in all, the level of freedom in China is just leagues ahead of North Korea, even if they both score poorly on indexes such as the Freedom House Index.

Takeaway #3: Progress on Censorship is not destined.

Last year I had dinner with a friend who I knew in Shanghai in 2012. This friend moved to the US around 2020, and told me that the arts and culture scene which had been so vibrant in early 2010s Shanghai had been dying. Finding space and getting approval for art exhibitions or movies was harder. More content was censored. People were afraid of films or concepts which could be even remotely seen as anti-government.

This, of course, only kicked into higher gear when Covid hit.

News reports seem to suggest that censorship really has been increasing in contemporary China. And one only needs to look at Hong Kong, where I spent many years, to see the dramatic effects of the new National Security law.

At the same time, I distinctly remember going to a nightclub in Hangzhou, China once, maybe in 2015 or ’16. I saw everyone drunk, laughing, happy, acting just like Americans or Europeans or really most people around the world, and I just realized how impossible it was for China to return to a North Korean-style society without nightclubs, with total control, with so little space for free time or thought. China is a fascinating country with many economic and cultural achievements, so it may also be just a matter of time before greater freedoms of speech take hold. It’s important to note that the free speech situation in “greater China” is very mixed with Taiwan being very free and to a lesser extent Hong Kong, having more permissive speech, showing a future with greater freedoms is possible.

My experience talking to friends and locals in the country gives me hope, even when considering the sobering results of the study we looked at above.

But what about censorship in the US and Europe? What are global attitudes towards censorship and free speech?

Free Speech Globally

It’s worth noting that the US and Latin America has, by global standards, unusually strong support for free speech.

This 2015 Pew Research survey across national boundaries found the US to be the world leader for free speech support, although it was second behind Latin America on media freedom.

I think that some of this effect merely results from people wanting to be proud of their own systems, their own countries, and their existing ways of life. People are the heroes in their own stories, and people want to belong. In most cases, we want to be proud of our cultures and countries and hometowns. (I’ll never forget the time I asked a Japanese local told me, with absolute conviction, that the most beautiful view in the entire world was in in the small Onsen town of Beppu.)

Some issues of free speech are also difficult philosophical issues which don’t necessarily have a clear answer. At what point does offensive speech become hateful, and at what point does that speech endanger people’s lives?

In Denmark, burning the Danish flag is legal, but burning foreign flags is not, which is an interesting philosophical position. Debates over flag burning are also alive in the United States, with both Hillary Clinton (in 2005) and Donald Trump (in both 2016 and 2020) supporting jailing flag burners. New Zealand, Germany, and Finland, which many think of as a very liberal countries, apparently ban flag burning showing certain activities are prohibited in many societies which are generally perceived as quite free.

Free Speech and Censorship in the US Context

The United States has robust free speech protections, but potentially worrying trends are emerging. Political divergences over the seriousness of offensive content online are one potential sign that support for freedom of expression may become politicized and possibly change in the future.

This chart is from Pew Research, and was from this article.

However, given the strong legal protections for speech, as well as the fact that parties in opposition nearly always want to support free speech (so they can criticize the party in power) I am mostly confident the US tradition of free speech will continue.

So What Can, or Should, “The West” Do About Censorship?

Maintain Our Freedoms

I think one of the most important things to do is maintain our own freedoms, whether that be freedom of speech, civil rights, voting, or other core freedoms for a modern society. If we don’t demonstrate the power and importance of free speech, and how it can help everyone in a society, we are failing. As evidenced by Clinton and Trump’s support for jailing flag burners, it is certainly the case that cracking down on some types of free speech can be a bipartisan issue.

I was in Hong Kong just after Trump fired James Comey as head of the FBI, and a couple from China I knew expressed incredulity that an American President would go so far as to fire the head of the FBI who, in their mind, had done nothing wrong by rejecting Trump’s desire for “loyalty”. It made me both proud and sad to consider that these friends looked to America for strong institutions and rule of law, only to see it seemingly slipping away.

Resist Lazy Stereotypes About Foreigners

It is also important to remember not to categorize every single member of a country, or group, as being responsible for the policies of that government. Many people want to be proud of their hometowns, their cities, their countries, their cultures, and often their pride is primarily non-political. We run the risk of dangerous backlashes if we automatically group people together with the policies of their leaders. Just as we have a 50/50 country in the States, other societies often have deep political disagreements. The difference is that in countries which experience large amounts of censorship, we may often not know or hear of the people who bravely resist the prevailing narrative. Criticism which is lazy or veers towards racial or cultural attacks will only provoke backlashes and plays into the hands of leaders who oppose freedom of speech.

What does Yang (2022) Suggest?

Yang (2022) notes that while Roberts (2020) suggests spreading greater knowledge of censorship as a means to fight it, Yang’s own results suggest that greater knowledge of censorship can bolster support for the regime—if done right. Roberts does note, in line with the class-skewed censorship I felt in real life, that regimes can use censorship for some people to divide and bolster the regime. This puts us in a tricky position if Yang’s analysis is correct. Yang pivots and suggests that those who oppose censorship should instead shift their efforts towards exposing the harms and problems that censorship can cause, rather than just merely raising awareness that censorship exists.

Final thoughts:

One critical point to repeat is that censorship, done right, may actually increase support for repressive governments. Before visiting North Korea, I assumed that everyone was anxiously hoping to be liberated. While many (probably most) people presumably do want to be liberated, it is important to know that the ruling elite in Pyongyang, as well as the most loyal and most privileged elements of North Korean society are well aware that if the government collapses, their lives might actually become worse. From the limited amount I could see as a tourist, it appears that the incentives for those at the top are to support the government. There is certainly, at a minimum, a collective action problem with a J-curve for elites.

Long story short, Yang (2022) suggests that censorship is more effective if it is broad, sweeping, and not just about politics. This makes sense intuitively, but also matches my experience in countries which are believed to have high levels of censorship. It’s also important to remember that freedoms like freedom of speech only survive with continuous support and care from citizens, and that United States is not perfect in this regard, although we can still be proud of our robust rights around free speech.

Other Notes:I want to thank everyone who signed up after our previous post was shared on Marginal Revolution, which was a true honor, as well as the many signups from Reddit. I was delayed with this edition due to my PhD deadline.

We also have merch available if you’d like to support the show, thank you to those who have already purchased: www.TheStudiesShow.Shop

That’s it for now. Thanks everyone!

Alex

Alexander Webb is a PhD student and freelance writer (New York Times, National Geographic) who started The Studies Show in February, 2023.

p.s. A version of this episode will soon be released on our YouTube Podcasts channel, with shorter variants on our Instagram, and TikTok. On YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok you can follow us @TheStudiesShow. You can see our archives on YouTube Podcasts back to March, 2023 as well as short video archives on Instagram and TikTok since February, 2023. Our earliest Substack post dates to February, 2023.

This is super fascinating!