🇬🇧 The British Empire as an A/B Test — Flags, Symbols, and Identity

What happens when the same empire runs across different cultures — and leaves behind different flags?

The British Empire and its consequences have been a _______ for humanity.

The word you instinctively put there is almost a Rorschach test for your opinions about the world we live in today.

From first principles, it’s striking: places as geographically and culturally distant as Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Singapore, and South Africa share a common legal system, language, and arguably a set of institutional norms. Even in India — no longer a colony — the fingerprints of British influence remain visible in the courts, education, and the enduring prestige of English among elites.

Of course, that influence came at a brutal cost. The British Empire’s rise involved extraction, subjugation, and violence. But it also created a strangely durable set of political and symbolic structures — and its institutional echoes still shape global systems today.

Seen from one angle, the British Empire was a kind of slow-motion A/B test: an experiment in exporting the same “code” — British law, governance, symbols, and infrastructure — into vastly different cultural environments. It wasn’t always intentional, but the effect is clear: different colonies, same institutional inputs, wildly divergent outputs.

Like an A/B test in software engineering, the variables were held constant: common law, the Union Jack, parliamentary design. But the “users” — local cultures, climates, religions, resistances — produced different responses. Some colonies rewrote the rules. Others kept them. Some evolved into democracies. Others did not.

Empire, in this light, wasn’t just conquest — it was a distributed experiment. And the remnants of that experiment are still visible today, not just in law or language, but in the flags flying over former colonies.

So let’s begin with the most visible — and perhaps least consequential — piece of the puzzle: flags.

It’s not just what’s on the flag, but what the flag is saying in the language of symbols: Who are we? Where did we come from? And perhaps most importantly, what parts of that story do we still want to fly over our heads?

We will briefly look at the flags of Australia, Hong Kong, Canada, The British East India Company, the US, and also discuss the politics around Australia’s flag debate.

This topic truly deserves an entire book length treatment, so consider this to be merely scratching the surface for further analysis.

First, let’s look at the colonial template, and the UK flag itself":

The Colonial Template

The de facto template for British Empire flags featured the Union Jack in the top left (the canton), with a local insignia or logo defacing the flag.

The prevalence of this format is vividly shown in this late ‘90s poster calling for the Australian national flag to be changed. This array of flags includes a fire brigade, colonies, Australian States, a US State (Hawaii) and more.

Here is another image further demonstrating the plethora of flags in use by the British Empire. Special note to the flag of British Indian Ocean Territory, (which includes Diego Garcia), which is one of the most beautiful flags I have ever seen.

The repetition of this format across such a vast geography reveals not just a design preference, but a worldview. It encoded the idea that no matter how far from London, each colony was still a visible extension of the crown — not just politically, but symbolically.

This symbolic reach was crucial. Long before colonists encountered British courts or bureaucrats, they often encountered British flags. It was an empire introduced visually before it was introduced legally.

Symbolism and the British Empire

Flags don’t just represent sovereignty — they project it. They tell you who’s in charge, what’s sacred, and what history is being remembered (or erased).

Flags are symbols. This is part of what makes flag debates so fraught — they aren’t just about cloth, or history. Flags are national symbols. They say something about our past, but they also say something about what we are choosing to permanently display today.

Political theorist Benedict Anderson famously argued that nations are “imagined communities” — socially constructed entities bound not by blood or geography, but by shared symbols, rituals, and narratives. Flags, in this framework, aren’t just markers of sovereignty; they’re part of the architecture that helps people imagine themselves as belonging to a common polity. The British Empire, in extending a flag template across continents, wasn’t merely asserting power — it was inviting its subjects (or imposing on them) a particular imaginative structure. To fly the Union Jack was to be folded into the fiction of imperial unity — even when reality was fragmentary, brutal, or unequal.

Consider the design choices of colonial-era flags. Almost all followed a template: Union Jack in the top left corner (the canton), and a local seal or symbol on the right. The formula was intentional — it visually reinforced the hierarchy: British supremacy in the upper left, colonial specificity as a side note. These were never meant to be equal compositions. They were signals.

In vexillology — the study of flags — placement and prominence matter. The upper-left canton is prime visual real estate. To place the Union Jack there was not merely conventional; it was imperial.

When a post-colonial nation keeps or modifies that format, it tells us something. It might reflect continuity. Or apathy. Or a belief that the past is inescapable — or even useful. Other countries choose radical breaks, often creating abstract symbols, new color palettes, or designs meant to transcend ethnicity or class.

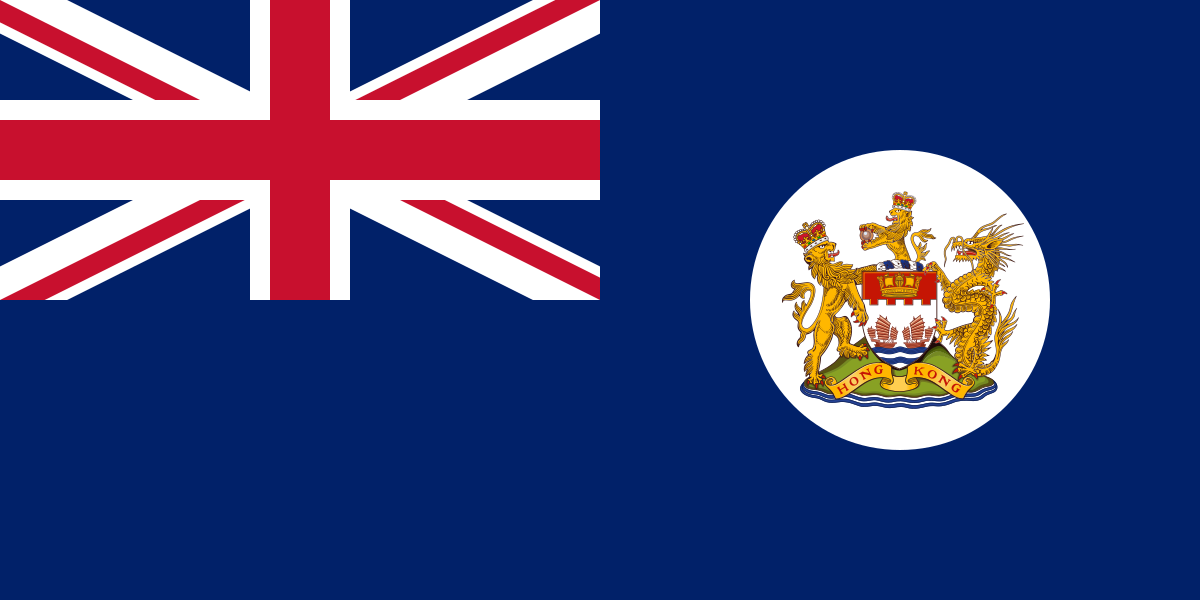

Hong Kong

The colonial Hong Kong flag changed multiple times, but often featured a British merchant doing business with local Hong Kong people, showing the importance of trade to this colony. The final flag, however, featured a coat of arms. What is notable is that even the post handover Hong Kong flag also bears similarities China’s national flag.

These colonial coats of arms often blended British heraldic tradition with local symbols — an attempt to visualize a hybrid identity. In Hong Kong’s case, the crest included a lion, a dragon, two Chinese junks, and a crown — a trinity of British monarchy, Chinese trade, and maritime power. Even in its symbols, the city was defined by its role as an imperial hinge point between worlds.

Scholar Homi Bhabha described colonialism as a space of blending and contradiction — where imperial powers tried to impose their culture, but often ended up absorbing local influences too. In this view, symbols like flags aren’t just about control; they’re also about negotiation. Hong Kong’s colonial flags, which paired British lions with Chinese dragons, are a perfect example. These were not clean, unified designs — they were hybrids. And that mix of identities didn’t disappear after the handover. The current flag, with its five stars echoing China’s national flag, still carries traces of its unique past, given that almost no city in China has its own flag, demonstrating—I think—a desire for centralized control. (That phenomenon deserves its own article!)

There are 5 stars making up the Bauhinia flower, matching the five stars on the Chinese flag (below). It’s an aesthetic of absorption — signaling that Hong Kong is part of the nation, not just legally but emotionally. Even its flower carries five stars.

Given Hong Kong was returned to China, rather than achieving independence like other former British colonies, it is not surprising its flag strongly reflects aspects of the Chinese national flag.

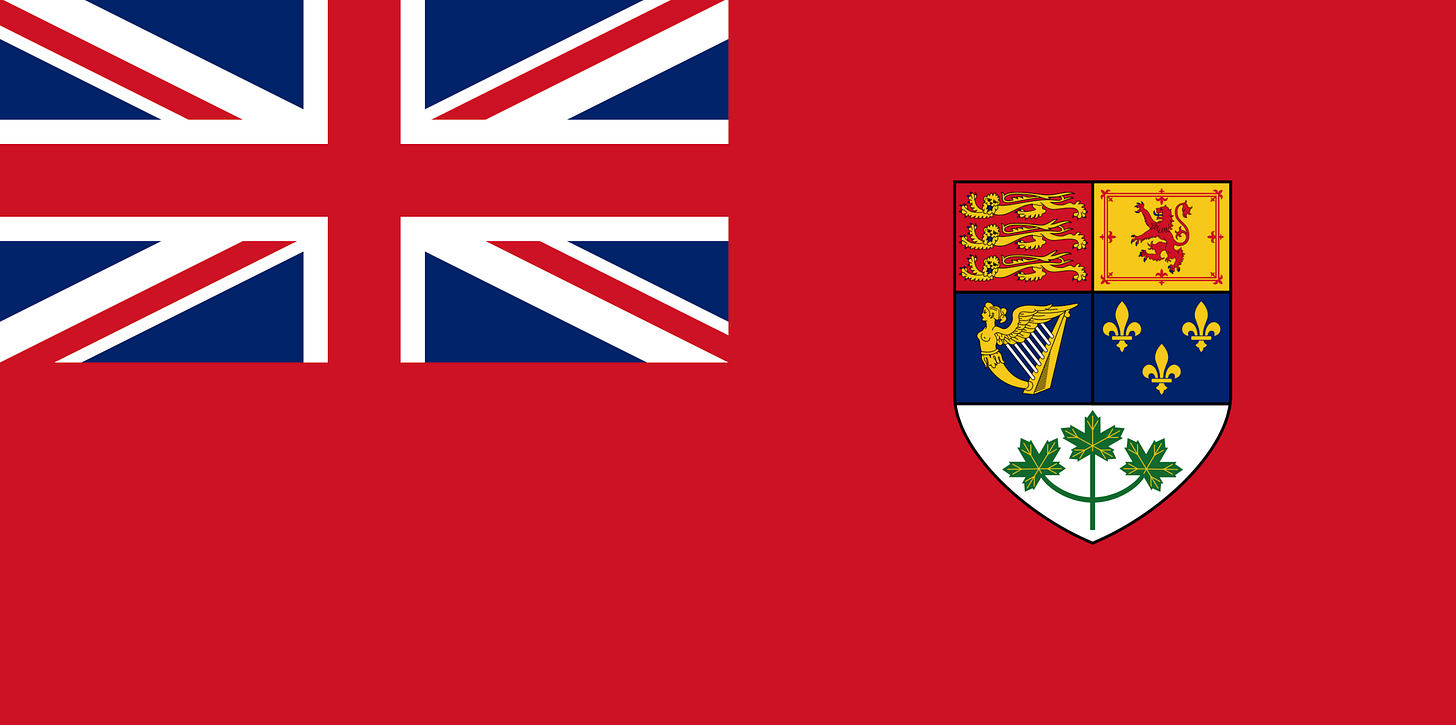

Canada

Although Canada’s iconic Maple-leaf flag is difficult to forget, until 1965 Canada’s official flag was simply the Union Jack. For the North American colonies which remained loyal to Britain, I suppose this is fitting, although it is important to note that various Canadian civil ensigns were popularly used to represent Canada. Usually a variation of this one, below:

The maple leaf flag is a good example of post-colonial meaning making. It’s clean, abstract, and emotionally resonant — a symbol that gestures both inward (toward national identity) and outward, with a clear image to present to the world.

The 1965 flag debate in Canada was bitter and deeply symbolic — a public reckoning with what it meant to move from “loyal dominion” to independent nation. The new design, stripped of colonial emblems, was both an aesthetic and political break. Some even called it the first truly post-colonial flag in the British world.

South Africa

If Canada’s flag was a symbolic evolution, South Africa’s was a rupture — and a rebirth.

Before 1928, British South Africa had a flag similar to other colonies. But from 1928 to 1994, South Africa’s national flag was visually and politically entangled with its colonial past. It incorporated the Dutch tricolor (referencing the Afrikaner population), and miniaturized versions of the Union Jack, the old Orange Free State flag, and the Transvaal Vierkleur — all placed at the center. It was a symbolic attempt to stitch together colonial factions, but in doing so, it entirely excluded the Black majority. The flag became a stark emblem of apartheid: a fractured, exclusionary national story told through symbols only a few could claim.

Then, in 1994, everything changed. South Africa adopted a new flag to mark its transition to democracy and the end of apartheid. The design was bold and unprecedented — a Y-shape reaching forward, with six bright colors but no dominant hue. It was designed not to reference any past statehood, but to symbolize convergence, plurality, and a collective future. In vexillological terms, it broke every colonial template. In political terms, it was the visual declaration of a new kind of nation.

The transformation wasn’t just aesthetic. It was foundational. South Africa’s new flag didn’t evolve from the old — it rejected it. And in doing so, it became one of the clearest cases where changing a flag truly did mean changing a country.

In contrast to places like Australia or New Zealand, where the debate remains unresolved, South Africa’s flag stands as a rare example of symbolic clarity — a clean visual break that mirrored a political one.

Australia

The Australian national flag is, essentially, the same as the colonial flag formalized in 1901. It features the Union Jack, the Southern Cross constellation, and the Commonwealth Star — a symbol representing the federation of states.

This flag remains unchanged, despite multiple referenda, proposals, and debates. Many Australians view the flag as a symbol of shared history and national unity — while others see it as a relic of colonial subjugation and erasure.

The tension here reflects a deeper conflict: Should the flag represent the dominant historical narrative, or aspire to represent everyone, including those dispossessed by that history?

On paper, Australia (and New Zealand) are seemingly perfect candidates for flag changes. They are distant from Britain and have strong movements that recognize the First Australians or First New Zealanders. But the plethora of options and different political symbols behind those movements makes any change complicated.

The debate in Australia has lasted decades, often flaring around national holidays like Australia Day, which many Indigenous people mark as “Invasion Day.” The flag debate isn’t just a matter of design — it’s a proxy war over history, recognition, and national origin myths.

While some have advocated simply changing the Australian flag to Aboriginal flag—to recognize the first Australians—complicating the situation in Australia is that there is also a separate flag for islanders in the Torres Strait (near Indonesia), making the adoption of the Aboriginal flag not a completely perfect fit.

In Australia it is common to see the National flag flying alongside both the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander flags.

Together, these three flags form a symbolic triangle — one of empire, one of Indigenous survival, and one of inclusion. But they also suggest a question: Can one flag ever speak for all three stories? Obviously, that is a hot debate and will likely remain one for a very long time.

The UK itself:

While Brits are likely familiar with the history, many outside the country do not know the composition of the British flag. As can be seen in this image, it is composed of the English flag, the Scottish Saltire, and Saint Patrick’s Saltire (representing Northern Ireland).

What’s remarkable is that this flag is itself a kind of symbolic federation — multiple nations, brought together through war, marriage, and conquest, unified under one symbolic cloth. The fact that the UK’s own flag is a layered compromise may partially explain its flexible deployment across the empire.

This philosophy — unity through layered symbolism — also informed the empire’s aesthetic abroad. This philosophy seems to have also informed Britain’s colonial activities overseas, where the British allowed for some degree of local self governance and control.

In other words, the very construction of the Union Jack — a layered, hybrid identity — became a kind of imperial template for managing difference through symbolic unity.

In the unlikely but possible chance that Scotland leaves the UK, the flag itself may have to change. It is possible that some post colonial nations will be flying the Union Jack longer than the UK itself does.

The Remarkable Similarities between the Flag of The British East India Company and The United States

Early in its history, the British East India Company (BEIC) used the flag of England with 13 (or 15) red and white stripes. Historians debate whether this flag influenced the design of the United States’ flag, with Ansoff (2011) rejecting the idea the US flag was inspired by the BEIC flag.

Nonetheless, the parallels are hard to ignore, making it an unusual coincidence if it really was one.

Later in the history of the BEIC, the below flag was adopted.

Although the flag above appears to be an American flag with a Union Jack, it is actually one flag used by the British East India Company. Note the identical number of stripes—13, as the US flag.

It is also almost identical to an early US flag known as the “Grand Union” flag, featuring 13 red and white stripes with a Union Jack in the canton. Above you can see the flag featured on North Carolina currency in 1776. This wasn’t just aesthetic. It symbolized loyalty to the British system — but a desire for autonomy within it. Independence came later. The visual timeline tells its own story.

It’s hard to overstate the symbolic weirdness of this flag. A nation about to fight for independence — doing so under a banner that still bears the insignia of the crown. It’s a visual paradox, a design echo of political uncertainty.

This created a kind of visual contradiction: the flag of rebellion was also a flag of continuity. Even as the American colonies prepared to sever ties, they signaled their belonging — or their right to belong — within the British symbolic world. They symbolized a belief in the importance of British values (or perceived values) of liberty and freedom (regrettably, in those times, a freedom not for most people). That ambiguity made the Grand Union flag unstable, and likely contributed to its short lifespan. Its successor, the Stars and Stripes, removed the contradiction while keeping the visual grammar — stripes, simplicity, unity.

Perhaps those tensions are why the flag was soon retired and replaced with stars in the canton, a general design that persists, amidst some changes, today.

What is funniest about this flag is that it would be great fodder for conspiracy theories. Imagine: the idea that the British East India Company never folded, it simply became the United States. In this era of trade wars, it is an increasingly good conspiracy theory, as these things go.

Is there a correlation between flag change and democracy?

Interestingly, there seems to be no clear correlation between democratic strength and flag change. Some of the world’s most stable democracies — like Australia and New Zealand — still fly variations of their colonial banners. Meanwhile, countries undergoing major political ruptures, like South Africa after apartheid or the United States during the revolution, have adopted radically new flags. This suggests that symbolic reinvention often follows ideological disruption more than steady democratic evolution.

Is the British Empire more of a franchise model, instead of an A/B test?

Although it’s tempting to compare the British Empire to an A/B test, it could also be looked at differently. The British Empire demonstrates how common institutions or institutional priorities interact with various local cultures, and various ways of governing. Arguably, this could also be seen as a kind of franchise model, much as McDonalds exists around the world but has its menu modified based on local taste.

The idea of some degree of local control and democracy—although not implemented everywhere—ironically led to the breakup of the Empire itself, as colonies like Canada and Australia achieved their own independence and created their own national identities. If it is viewed as a way of spreading institutions and ideas, the British Empire lasted as long as it reasonably could have.

Final Thoughts

Flags may be cloth, but they’re also code — visual systems for encoding identity, power, and aspiration. In that sense, they are a perfect starting point for exploring the legacy of empire. The flags we’ve looked at here do not just mark geography; they reveal how Britain’s symbolic influence was exported, refracted, and sometimes resisted. From Hong Kong’s colonial banner symbolizing trade, to the Grand Union’s strange half-loyalty, each flag tells a slightly different story of adaptation and ambiguity.

This comparative lens — who kept the symbols, who modified them, who rejected them — is a diagnostic tool. If empire was an A/B test, then the flags are datapoints. The patterns we see here will echo again as we examine law, language, and governance. Same empire, different results.

But symbols are just one part of the story.

Future entries in this series will explore the non-visual legacies of empire: how the British legal system embedded ideas of property, contract, and hierarchy; how English became a dominant linguistic currency across the world; and how even ideas of “civil society” and “development” were shaped by British norms. The symbols matter — but they were always backed by rules, institutions, and incentives. And those, too, were exported.

And by looking at how those institutions performed, we may get a clearer sense of what the British Empire really was: a sprawling, contradictory experiment in governance, belief, and control. Flags aren’t everything—they aren’t even that important. A country can change its flag and still leave its power structures untouched. But by tracing how these symbols evolve — and when they don’t — we begin to see how injustice is remembered, forgotten, or rewritten through visual language.

In an age of global nationalism, contested histories, and shifting power, these symbols remain charged. They show up on football kits, in protest movements, on beaches, in schools. We live in the long shadow of empire — and sometimes, we live beneath its flags.

Thank you for reading The Studies Show, we have been creating content under this name since February 2023 and you can find us on YouTube and YouTube podcasts @thestudiesshow as well as on Instagram @thestudiesshow

Thank you to everyone who made it this far, it means the world and I really appreciate every reader/viewer and every comment.

Until next time! Alex

It's striking how much modern Canadian sources present the new flag as 'inevitable', or at least portray the opposition as a small minority who either didn't know what was good enough for them, or maybe weren't really Canadian at all.

But then the whole point was to re-write Canadian identity, and it succeeded so far, that many people can't imagine that anyone saw it as something being taken away from them, rather than an imposition being lifted.