EVs are a Defense Strategy for China

After the capture of Maduro, the promotion of EVs in China is even more heavily informed by security implications.

Note: This article was written before the capture of Maduro, but has been updated given Venezuela was an important ally and source of oil for China.

I recently visited Shanghai, and what they say is true—there are electric vehicles everywhere, it feels like the future, and going back to the US or Australia feels like stepping into the past (at least when it comes to cars).

While many people talk about the shift to EVs from an economic or green energy strategy, I think the motivation for this shift is really a national security strategy, even if other factors matter too. Here are three reasons why, preceded by a related story about the Beijing Olympics.

The Story

In 2008, I lived in Beijing just before the Olympics. I asked a taxi driver, in broken Chinese, whether he liked Hu Jintao or Wen Jiabao more. (These were the top leaders in China at the time.) He gave a vague answer, saying some prefer one, some prefer the other. Another taxi driver said they were both good. Another refused to talk about it.

I was surprised, since I thought that a taxi driver, accustomed to meeting foreigners, driving in a private car, might be willing to speak a bit more freely. And I never asked them to criticize either leader. But I was wrong.

Eventually I learned why. As reported in the Wall Street Journal, the taxi fleet had been outfitted with remote controlled microphones and GPS systems, which enabled the remote shutoff of the vehicle, as well as monitoring of the conversation.

These same incentives, as well as others we will soon get into, are one reason I believe China has embraced electric vehicles.

The National Security Advantages of Electric Vehicles for China:

China is vulnerable to an oil blockade, EVs (partially) solve that problem.

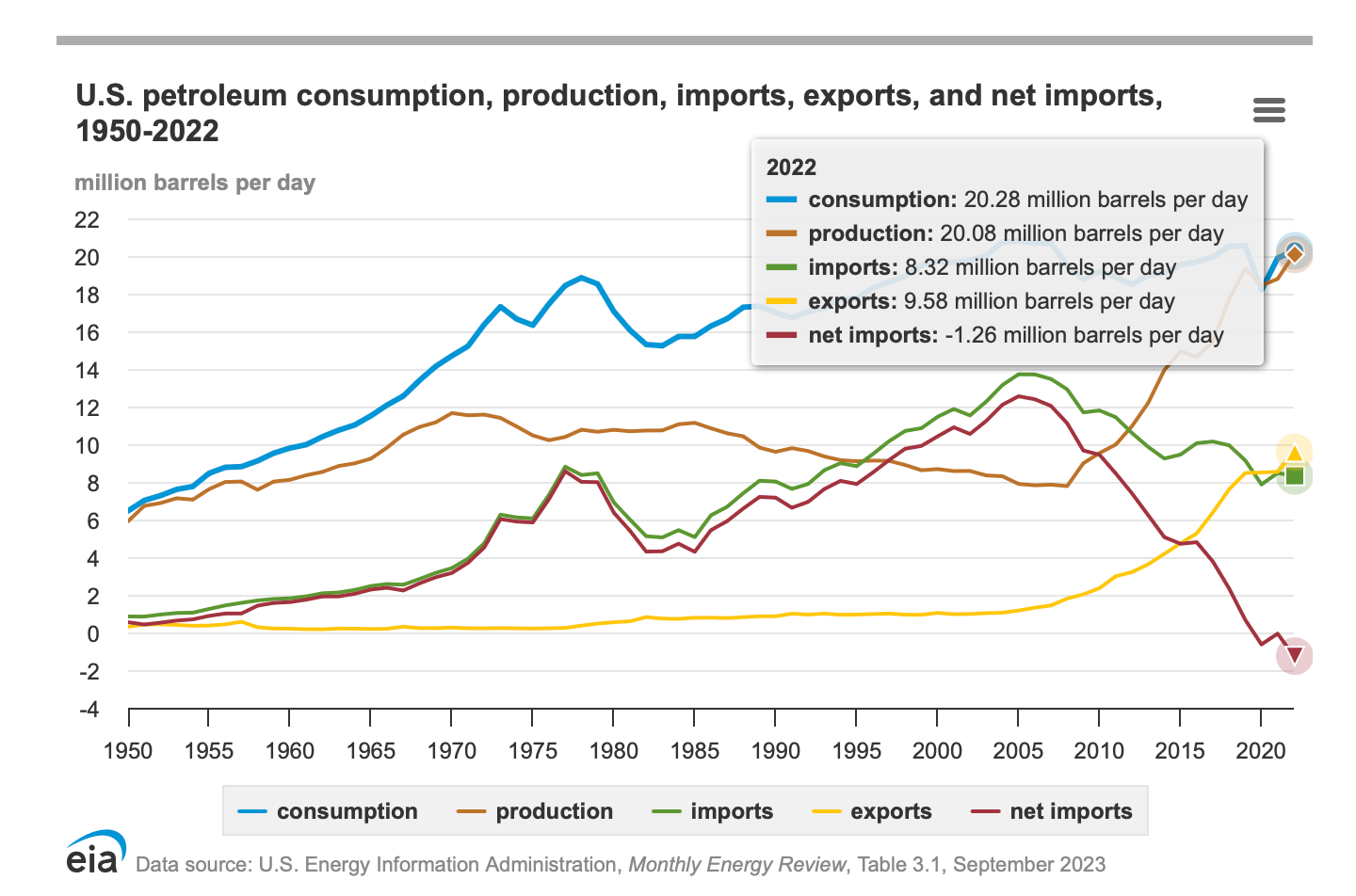

The United States produces 3x as much oil as China, despite having a 4x smaller population. It also is a net exporter of petroleum. In a crisis, the US could survive on its own production if it had to.

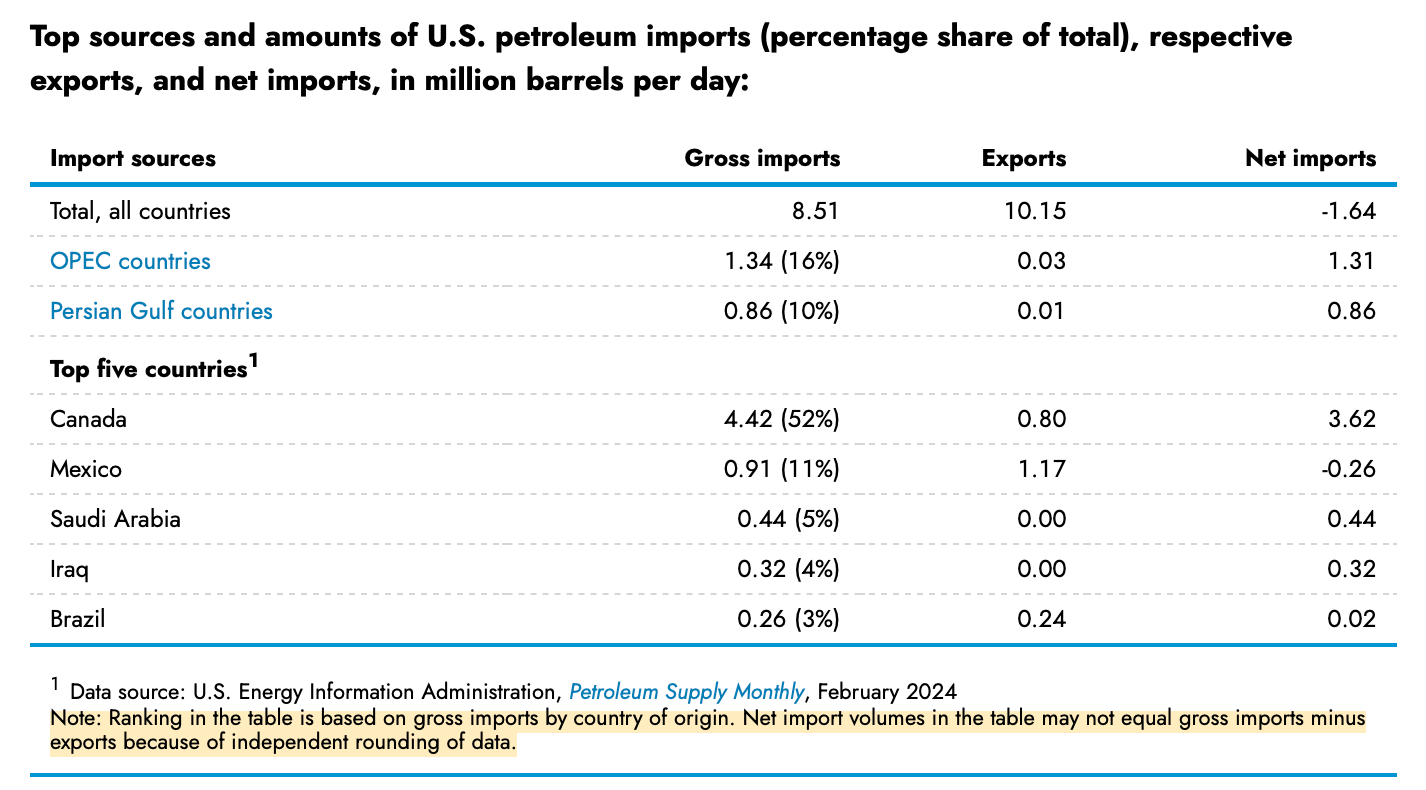

Meanwhile, over 60% of US petroleum imports come from Canada and Mexico, which are unlikely to stop supplying the US in a crisis.

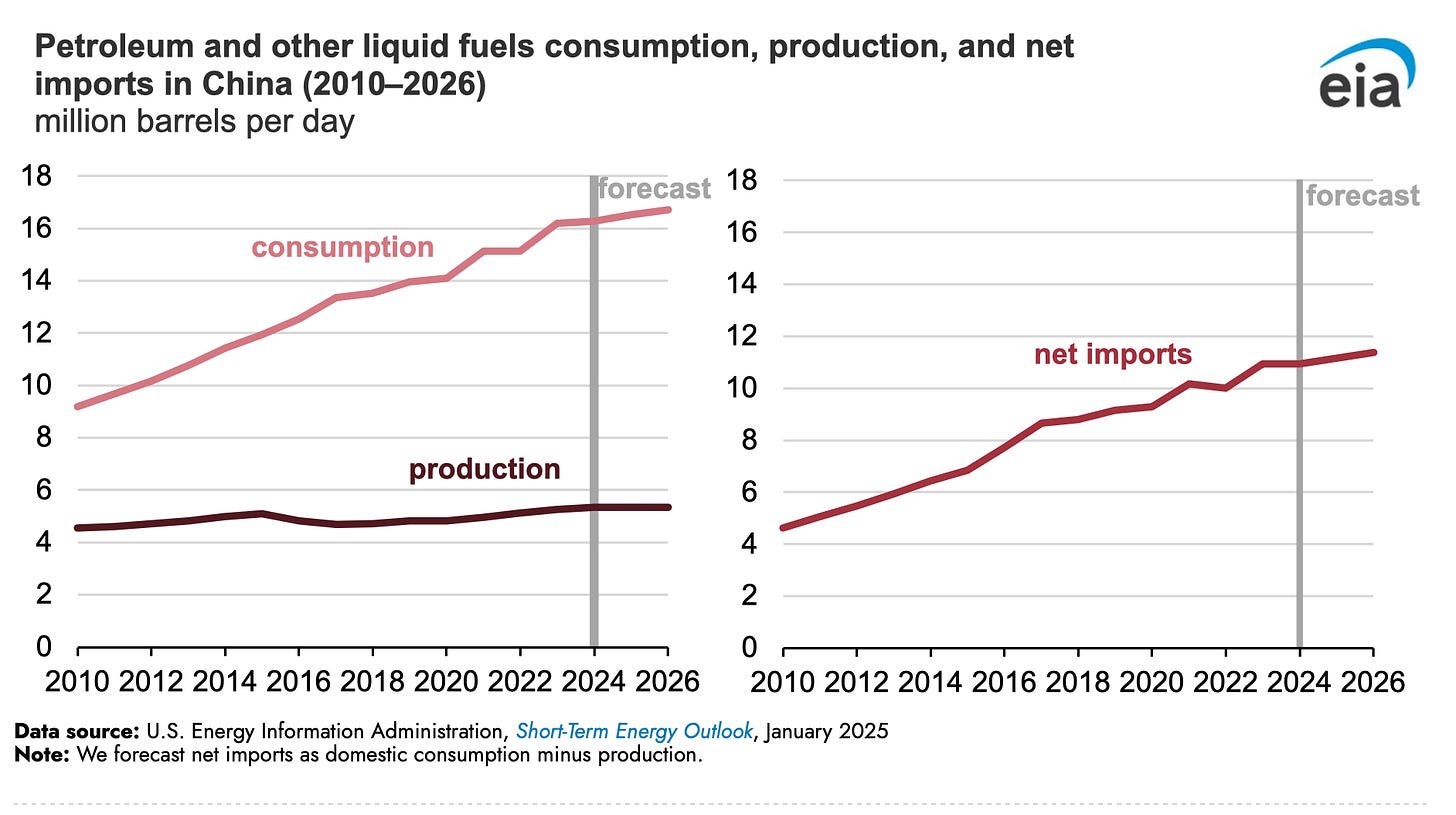

China, on the other hand, is consuming almost as much Petroleum as the United States, but is far from self-sufficient. Around 1 million barrels a day of China’s petroleum come from the United States, meaning a small but real amount of Chinese consumption could be shut off by American action alone.

Given the loss of Venezuela as a close ally and semi-reliable supplier of oil, China is only further incentivized to pivot to electric vehicles. It is likely that, in a true crisis, only Russia could be counted on to continue to sell oil, given their overland pipelines.

These factors mean that diversification towards electric vehicles makes much more sense for China from a national security standpoint. While the US could survive a global oil crisis based on local production, this apparently would not be the case in China without painful consequences.

Interestingly, China has been stockpiling oil for months. It could be for price reasons, or other ones entirely.

China controls the EV tech stack, and associated fields, like solar panels, enabling cheap power generation without imports.

China’s massive investments in solar panel and battery production means that the country is not just skilled at making EVs and associated green energy generation technologies, but also that these purchases support local companies and supply chains.

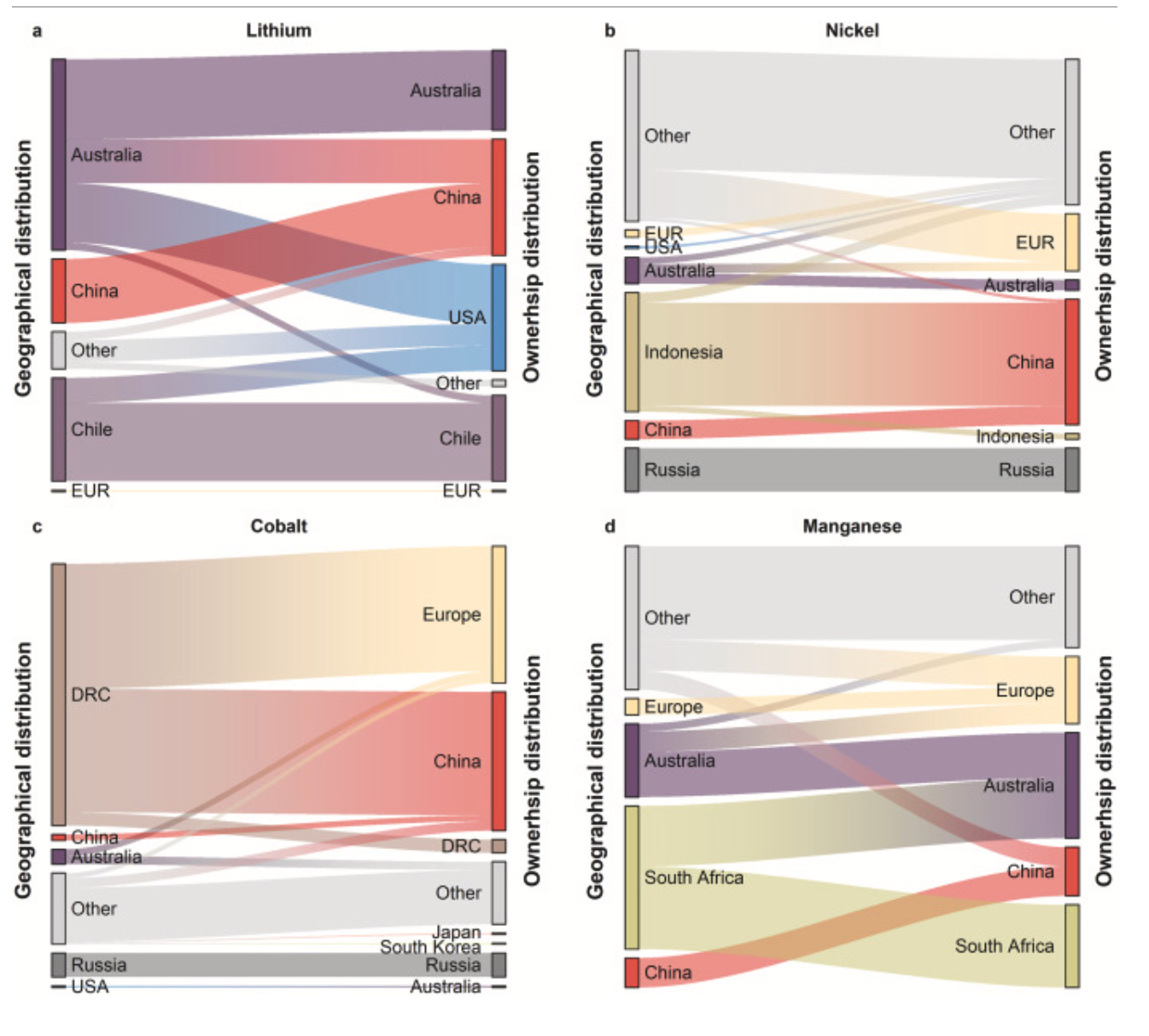

China has wisely invested across the world, buying crucial stakes in foreign mines.

For example, in China’s hold on the lithium-ion battery supply chain: Prospects for competitive growth and sovereign control by Greitemeir et al. (2025) we find these golden quotes and charts demonstrating just how well China has played the game:

*With regard to nickel mining, approximately 30 % of global production is located in Indonesia, establishing it as the leading region. Out of its own production share, a mere 4.77 % is currently owned by Indonesian companies. Meanwhile, China has a dominant presence there, holding an impressive 86.73 % of the Indonesian mining rights, thus ranking first in terms of ownership of global nickel production.*

As we can see, While China is blessed with a relatively strong supply of Lithium and Manganese, it has made up for lacking other inputs by aggressive purchases of mining rights across the world.

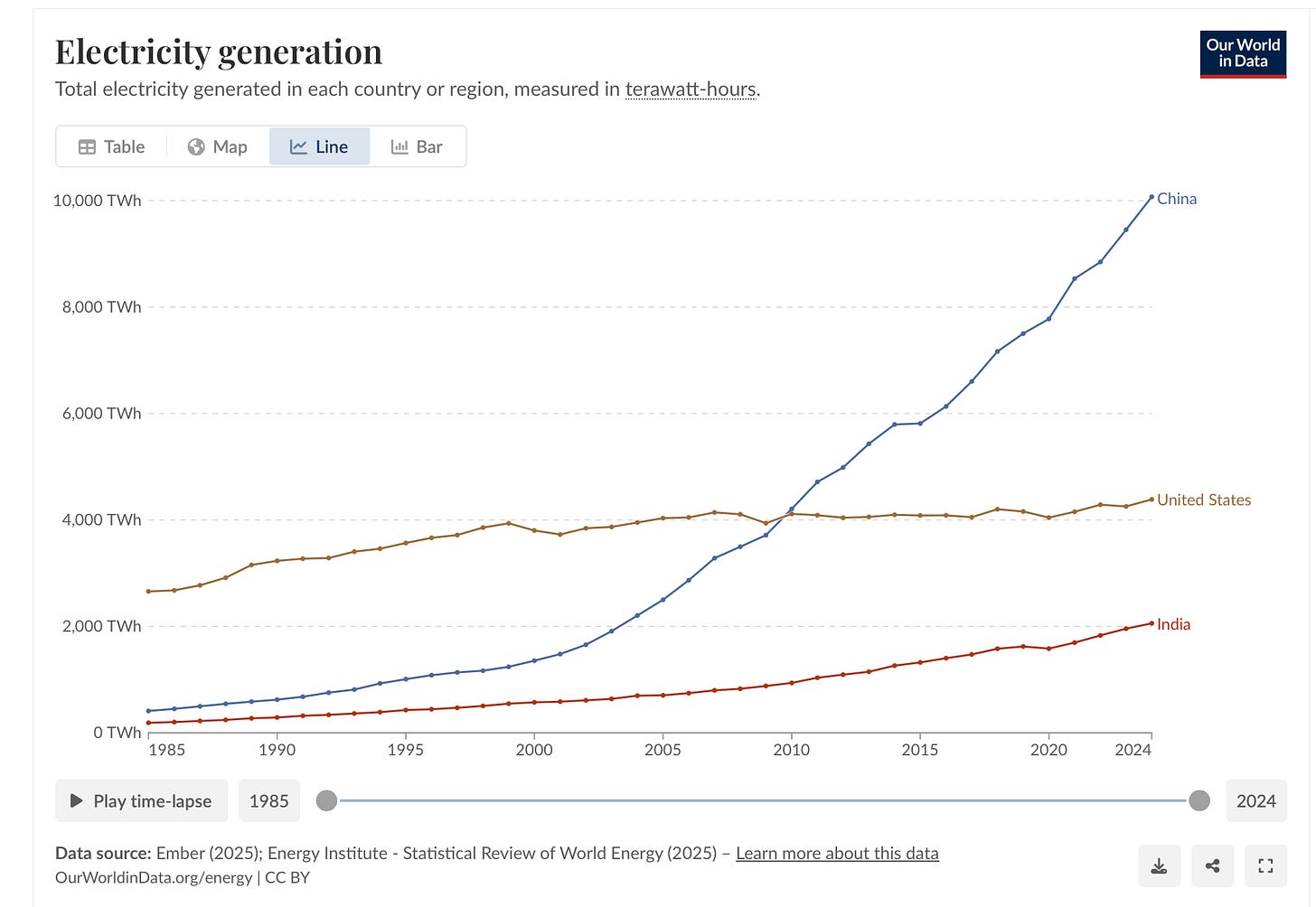

Meanwhile, China has generated more electricity than the United States since 2010, and now dwarfs the US in electricity production. Some of this is for manufacturing, and much of it is coal, but the fact the supply exists allows the country to power EVs in a crisis. In 2024, China installed more solar than the US has in its entire history, and dominates production of photovoltaics.

As we can see in this chart from the International Energy Agency, China absolutely is unmatched when it comes to Solar photovoltaic manufacturing.

EVs can be remotely updated, enabling control if the government wants it.

An all-digital, internet-connected vehicle can be remotely shutoff if needed—something basically impossible with older gas-powered vehicles. And if this was selectively done in Beijing taxis in 2008—nearly 20 years ago—just imagine what is possible across modern EV fleets now.

These concerns are widespread and not unique to China. Europeans have worried about the US possessing an F-35 kill switch. Meanwhile, as reported in the Financial Times, the UK is now actively investigating alleged kill switches on Chinese-manufactured buses. These buses, or a variant, have also been sold in Australia.

From a national security angle, cars are one of the few deadly weapons capable of mass killings that an average person could possibly obtain. The ready sale of gasoline is one of the few ways an average person can obtain a highly flammable liquid suitable for use in a bomb. (NYC has had close calls with car bombs before, and China has had numerous car attacks, even if they are suppressed in the media). Philosophical differences around guns and knives already show that certain nations are more comfortable with average citizens having access to deadly force than others. From a national security lens, for a country like China which is more focused on security, this is a natural extension and is a key advantage of an EV-led transport system.

To be clear, while this article focuses on China, it is likely that major government has at least considered EV backdoors for security reasons. This is totally speculative, but two decades hence, there will probably be geofenced no-drive areas where it is impossible to take an EV, even in democracies.

All in all, these factors lead me to believe that EVs and their success should be looked at through a national security lens.

A national-security first focus would also explain some of the storm clouds we’ve seen. While Chinese EV sales have recently cracked 50% for the first time, we’ve also seen reports of overcapacity and financial shenanigans, suggesting the market is due for a correction. Regardless of whether there are problems in the short or medium term, national security incentives will likely push China towards an EV future faster than the US.

Some final notes:

Last but not least, they’re really nice:

Many Chinese electric vehicles are super nice. That Huawei store I went to in Shanghai was selling a fully loaded SUV for $45,000 USD with TVs everywhere, sumptuous seats, connected everything, etc. etc. It makes sense why Biden put 100% tariffs on Chinese vehicles. They’re just very good.

Long story short, the transition to EVs enables many things that fits the Chinese model of development. It prioritizes national security while also delivering reduced pollution and reduced dependence on foreigners. It helps ameliorate an energy weakness, and the cars are also actually nice, improving people’s standard of living.

Thus, from the perspective of the Chinese government, the EV transition is a big win from many angles, but especially from a security perspective.

The Studies Show was founded by Alexander Webb, PhD, in early 2023. Alexander Webb has also written for The New York Times, National Geographic, WIRED, Business Insider, and other publications, in addition to co-authoring multiple peer-reviewed academic papers.

Just to be clear, are you suggesting that China could turn off EVs remotely, or take control of them and use them for attacks?