How Bob Dylan, Housing Prices, and Harvard show that Networks Matter

Dylan's journey from unknown to icon illuminates a broader truth about success: networks matter, and access to them is becoming increasingly restricted.

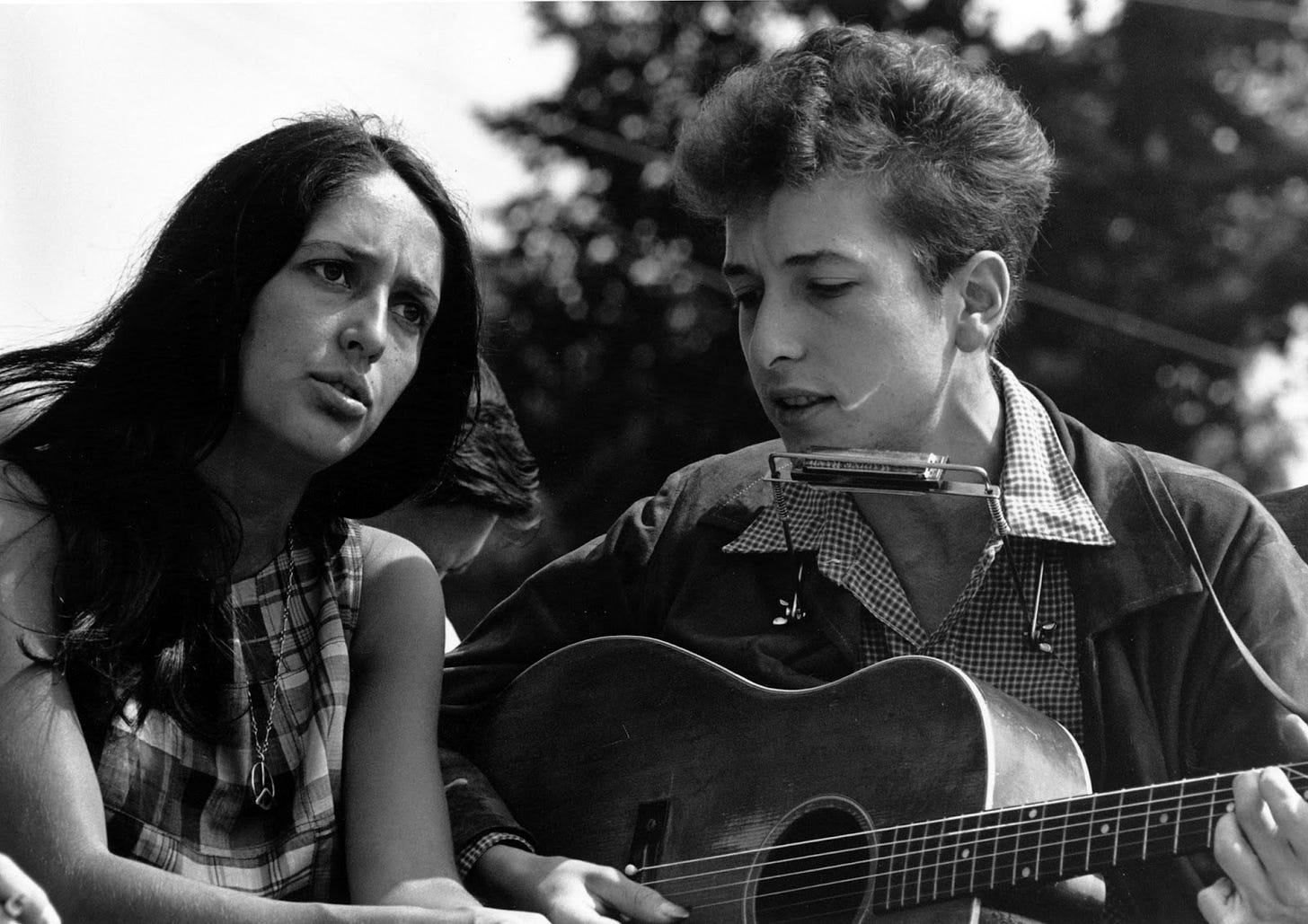

In January of 1961, a college dropout named Robert Zimmerman moved from Minnesota to New York City. He slept on couches before renting a cheap apartment, and soon found a place for himself in the local folk music scene. Zimmerman played harmonica on a friend’s album, which introduced him to John Hammond, the album’s producer and a talent scout at Columbia Records. He signed Zimmerman, who released an album in March 1962. It was mostly covers, with only two original songs. It sold a mere 5,000 copies, barely breaking even. Some at Columbia Records wanted to drop him, calling Zimmerman “Hammond’s Folly.” John Hammond defended him, and encouraged the young artist to release another album. In August of 1962, Zimmerman legally changed his name to Robert Dylan, and next year released an album of classic songs, including Blowin’ in the Wind. In less than two years, a broke dropout had transformed into the “voice of a generation.”

Bob Dylan is such a seminal figure in pop culture that it’s impossible to imagine a world without him. But what if New York City rents had been as high as they are today?

In December of 1961, Dylan and his then girlfriend—who appears on the cover of his first album—rented an apartment in the West Village for $60 a month, equivalent to about $597 in 2023 dollars. In today’s New York City, real rents have gotten much more expensive. In today’s West Village, the average one-bedroom rental price is about $5,000. The cheapest one bedroom I could find was $2,900, (there was also a single available studio for $2,750. Were Frank Sinatra still alive today, perhaps he would sing, “If you can make rent here, you can make rent anywhere.” Of course, today’s Dylan might live in a cheaper part of Brooklyn, or even Jersey City, but even there, rent is at least double in real terms what Dylan paid for his apartment. Dylan’s artistic troubadour lifestyle, which enabled him to write songs instead of spending all his time waiting tables, would be almost impossible for anyone without independent family wealth. Rent today is so unaffordable that Dylan might never have moved to New York—changing the trajectory of popular music as we know it.

If Dylan had never moved to New York, he never would’ve made the connections that jumpstarted his career. He never would’ve met John Hammond, the talent scout who took a massive chance on an unknown artist who hadn’t even written any of the songs that would later make him famous. To be sure, we now know Bob Dylan is a genius—but he wasn’t a genius yet. The right connections at the right time were the ladder that helped turn a talented nobody named Robert Zimmerman into the legendary Bob Dylan. (Hammond himself became a legend in his own right, and was crucial to the careers of Leonard Cohen, Bruce Springsteen, Aretha Franklin, and others.)

Dylan was lucky. He was born at a time when a lower-class individual could afford to move to the big city with only a dream and a few bucks. Today, even a cursory look at rental prices–which have increased dramatically in real terms–show how that is increasingly impossible.

Although he was no folk singer, my grandfather’s story has some similarity to Dylan’s. My grandfather was a Black man from Alabama who never made it past 2nd grade, and was functionally illiterate. Despite this, he moved to New York City and lived in a brownstone in Brooklyn, where he worked as a longshoreman. He lived in an age where poor people—and he was, truly, born into poverty—could move to big cities and gain a better life. Today’s high rents, coupled with well-intentioned educational barriers, makes that largely impossible today. His story is all the more remarkable when you consider that, as a Black man in the era around Jim Crow, he faced other major obstacles to economic security.

Ganong and Shoag’s 2017 paper, titled “Why has regional income convergence in the U.S. declined?” explains why stories like my grandfather’s, and perhaps Bob Dylan’s, are increasingly impossible. If you were born poor in a rural part of the country, you could once make a better life for yourself by moving to the big city. Today, the opposite is true.

The paper notes that while Janitors nominally make 28% more in NYC than in the Deep South, once you account for higher rents, they actually effectively make 7% less. Janitors spend 52% of their income on rent in NYC, while Lawyers, on the other hand, spend 21% of their income on it. This just demonstrates a fact of modern American cities–white collar professionals continue to price out lower-earning individuals. This has effects on the whole country, because people like my grandfather now have fewer economic opportunities. It is probably one reason why Americans are moving less today than they did in past decades.

And while Ganong and Shoag don’t talk about folk singers, we can see that Bob Dylan’s real rental costs went up perhaps 4 or 5 times. How many artists today are shut out of the industry because they couldn’t make connections? How many people in poverty are stuck, without a place to go? Ganong & Shoag’s results suggest that poorly educated people are increasingly cut out of America’s urban cores.

Janitors and longshoremen aside, you might say the music industry is different, and a contemporary Bob Dylan could just release his own albums, and hope to find an audience on the internet. Indeed, technological change has also altered how musicians are found. From Justin Bieber’s first viral video, to Desiigner’s 2016 hit “Panda” to the politically-infused viral success of Oliver Anthony’s song “Rich Men North of Richmond”, or Lil Nas X’s country-rap anthem “Old Town Road” there are viral success stories. But, out of those four artists, the only two with any staying power—Bieber and Lil Nas X—were embraced by major labels and turned into stars. Many other artists in the modern era made it by networking and meeting big stars in big cities. J.Cole moved to New York where he caught the attention of Jay Z. Kanye West started with Jay Z in a similar fashion, although as a beatmaker (I highly recommend listening to Kanye's “Last Call” which is about this story, and the last 5 minutes of the song is just him talking about moving to New York and trying to make it in music. Incidentally, J.Cole has his own version of the same song.) And, as many know, Taylor Swift worked hard but also had a wealthy father who helped fund her dreams, including purchasing 3% of the record label that signed her for $120,000.

It is telling that even superstars with no ostensible need for a label deal continue to partner with labels. Consider Kendrick Lamar, probably the hottest artist of 2024, who continues to partner with a label, even though he has his own company, PgLang, and has buzz so strong that he almost certainly would’ve had massive sales without such a partnership. Taylor Swift remains partnered with a label, despite ostensibly not needing one. But why? I have a guess.

Fascinating work on self fulfilling prophecies in music by Matthew J. Salganik and Duncan J. Watts (2008) helps explain why artists like Kendrick Lamar and Taylor Swift stick with labels despite their massive success. In an experiment with over 12,000 participants, they found that a song's perceived popularity had a huge influence on whether people would even give it a listen in the first place. But here's where it gets really interesting: when the team artificially manipulated download counts by completely flipping which songs appeared popular, they found that while some of the highest quality songs could partially recover their standing, the process was inconsistent and incomplete. Even good songs could end up with widely varying levels of success based on initial conditions and social influence. While this study was done in the download era, not the streaming era, I think it is likely the results still apply.

To make a slight leap from the paper, which song would you bet is going to be more successful: A pretty good song by Taylor Swift, released everywhere by a major label, or a fantastic song self-released by a nobody with 100 followers?

This might explain why even megastars who seem to have transcended the need for label support still choose to stay signed. Their research suggests that maintaining popularity isn't just about having good music; it's about keeping up the perception of popularity that creates self-reinforcing success. Labels provide that network of constant amplification across radio, playlists, press, and social media. Going independent would mean having to rebuild that entire ecosystem of attention-driving mechanisms from scratch, which might be more expensive and risky than sharing revenues with a label that already has all this infrastructure in place.

As Salganik told me for an article I wrote for WIRED, "Our research is both optimistic and pessimistic. In our experiment we found that better songs did better on average so I guess that's the optimistic part. But, we also found that there was a big range of possible outcomes, even for the same song. So, sometimes a good song could get unlucky." That uncertainty might help explain why artists often stick with the more predictable path of label support rather than gambling on maintaining their cultural position alone. Even for superstars like Kendrick and Taylor, the risk of going it alone might outweigh the reward.

The music industry's network dynamics reflect a broader societal pattern. While Bob Dylan needed physical proximity to industry connections, success in most fields similarly depends on network access, even in the digital era. Cities are the ultimate embodiment of this reality - concentrated hubs of opportunity where connections compound. But today's housing costs create barriers to accessing these crucial urban networks.

Big Cities are Networks

Big cities are the most productive places on earth, with a direct correlation between population and productivity. Big cities also have higher average salaries than the countryside. That’s why its so damaging for lower class people to be cut out of them.

David Autor’s 2019 paper "Work of the Past, Work of the Future" discusses a seeming paradox:

US cities today are vastly more educated and skill-intensive than they were five decades ago. Yet, urban non-college workers perform substantially less skilled jobs than decades earlier. This deskilling reflects the joint effects of automation and, secondarily, rising international trade, which have eliminated the bulk of non-college production, administrative support, and clerical jobs, yielding a disproportionate polarization of urban labor markets.

This, in turn, has reduced wages for poorly educated people, harming the American dream for those who don’t have fancy degrees. Were my grandfather alive today, he would benefit from a less racist society, but possibly earn less in real wages if he lived in a big city. (Of course, the picture is complicated.) The above chart from the paper shows how real wage gains have exploded for those with graduate degrees, but barely changed for poorly educated men. Women are doing much better, but a divergence persists.

Moving to a big city transformed my grandfather's life. And while his story shows how cities can create opportunity for anyone, the value of urban clustering is even more profound for knowledge workers. Enrico Moretti’s 2021 paper “The Effect of High-Tech Clusters on the Productivity of Top Inventors” demonstrates that inventors create significantly more patents when surrounded by other top inventors. Even though such highly productive individuals can usually afford urban rents, today's extreme housing costs must still prevent some talented people from accessing these innovation clusters. This suggests we're not just losing individual opportunities, but the compound effects of creative minds working in proximity.

How much is this costing the US economy as a whole? A famous paper (Hsieh and Moretti, 2019) estimates the US economy would be almost 3.7% larger if only San Francisco, San Jose, and New York City had zoning laws that were less restrictive1. Amazingly, 40 percent of Manhattan buildings standing today would now be illegal to build, hinting at the vast extent of our zoning problems. So why aren’t zoning laws less restrictive? Existing homeowners have no incentive to increase housing stock. In fact, they benefit from exclusionary zoning laws that increase the value of their real estate. But while existing homeowners profit, everyone else loses. The United States, long a country famed for internal migration, has in recent decades had the lowest rate of migration since record keeping began in 1948. Fewer people are moving—which means they aren’t following jobs to the most productive areas of the country. Staying put in dying towns or unproductive regions has big consequences. While mortality has dropped across the developed world, middle-class American whites, many of them stuck in moribund rural areas, have been dying at accelerated rates.

In 2016, in the midst of a tech explosion minting new millionaires and creating tens of thousands of well-paying jobs, the San Francisco Bay Area experienced a net outflow of 26,000 people. An exodus in the midst of an economic boom is an obvious sign that something is deeply wrong.

It’s baffling, until you look at housing costs. East Palo Alto, a city in the heart of Silicon Valley, has had a median home price of around $1 million dollars for the past five or so years. In 2012, that figure was only $277,000. In Mountain View, home to Google, the median price is about $1,900,000. In 2023 the US average is about $400,000.

Overzealous zoning laws that inflate housing prices restrict the ability of lower class workers—not to mention aspiring folk singers—to move where the most productive jobs are. That means only the rich or the lucky can easily take advantage of the 21st century’s best opportunities. We’ll never know how many entrepreneurs tried their luck in Silicon Valley, but had to leave before their big break because they couldn’t afford rent. From London to Sydney to Hong Kong, the stories are the same. Too much income is being spent on rent, and young people are locked out of a real estate market that—for the previous generation—generated large amounts of wealth.

Living in a big city can create a professional network that propels your career for decades. Moving to the big city is a way to reinvent yourself and develop new professional connections. The ability to live in the centers of economic growth is an increasingly large invisible advantage that benefits the wealthy and the lucky, providing them with connections and opportunities unavailable to others.

Never forget that Steve Jobs was only 12 when he called local computer company HP to ask for parts. This got him a summer job, and eventually led him to meet Steve Wozniak. Perhaps he would’ve been successful had he grown up in rural Wyoming, but he likely wouldn’t have been in tech. Jobs was adopted, and his adopted father was a high school dropout and son of a dairy farmer. He grew up in what was then an affordable house, but is today valued around $3 million.

Tim Cook, the current CEO of Apple, was born to a shipyard worker (perhaps his father and my grandfather could’ve been friends) and graduated from a public high school in Alabama. He apparently got into the tech industry when an I.B.M. recruiter visited Auburn, demonstrating the importance of chance connections (and his hard work). We will never know how many potential Steve Jobs or Tim Cooks will never be found because of their lack of proximity to, or brushes with, elite networks. While technology (like the iPhone and FaceTime) does make it possible for those at the periphery to make connections to elite networks, it does not seem to be the same as being truly embedded in those networks.

Housing in big cities is one example of an artificially constrained supply meeting extreme demand. This also exists in elite educational institutions, which could, if they wanted to, dramatically expand enrollment.

Elite Universities as Networks

While universities will claim that their mission is to educate the next generation, the fact that elite schools with enormous endowments have chosen to remain small suggests that part of their mission is to maintain the exclusivity of their degrees, and the value of the resulting social network.

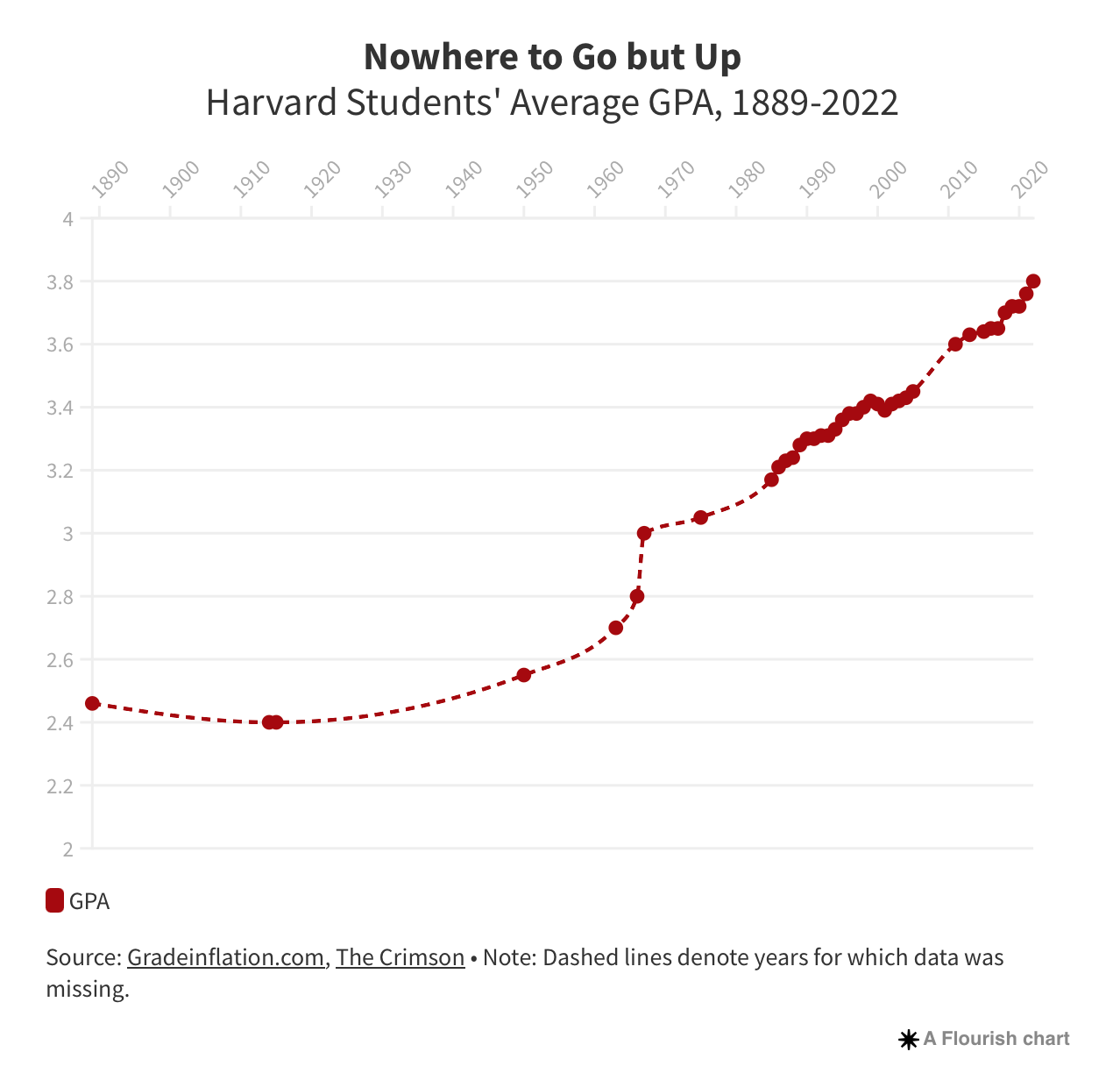

Further suggestive evidence of this phenomenon can be found if we examine grade point averages. A truly rigorous school focused only on learning might grade on a curve, or have a demanding course load which puts the smartest students to the test. Yet, at Harvard, this is not what we find.

The average Harvard GPA has risen inexorably for decades. Just look at this shocking chart:

The same article states that while getting on the Dean’s List was once an honor, 92% of students qualified the year before it was abolished. Even if one charitably assumes Harvard students are uniquely talented, the lack of differentiation between students is probably troubling from a strictly educational perspective. (I am also not sure we can assume this, given 32% of the class of 2027 seems to be legacy admissions). But if we assume that the point of getting into Harvard or a similar school is mostly to gain status and a social network and then leverage that into a career in consulting or finance, then the grade compression makes much more sense. Especially if we consider that Harvard (and many other universities) have a sort of symbiotic relationship with their alumni given many are heavy donors to their schools.

One could argue that, perhaps Harvard has simply admitted the smartest students, and so they are all doing fantastic. Yet this is not consistent with historical GPAs. Harvard was still an elite school 80 years ago, and this phenomenon did not take place. From the outside, it appears that Harvard is a fantastic school which nonetheless has internalized the reality that it is primarily a network building institution, with a great school attached to it. Furthermore, the fact that perhaps 25% of students are legacy admits seems to support this fact.

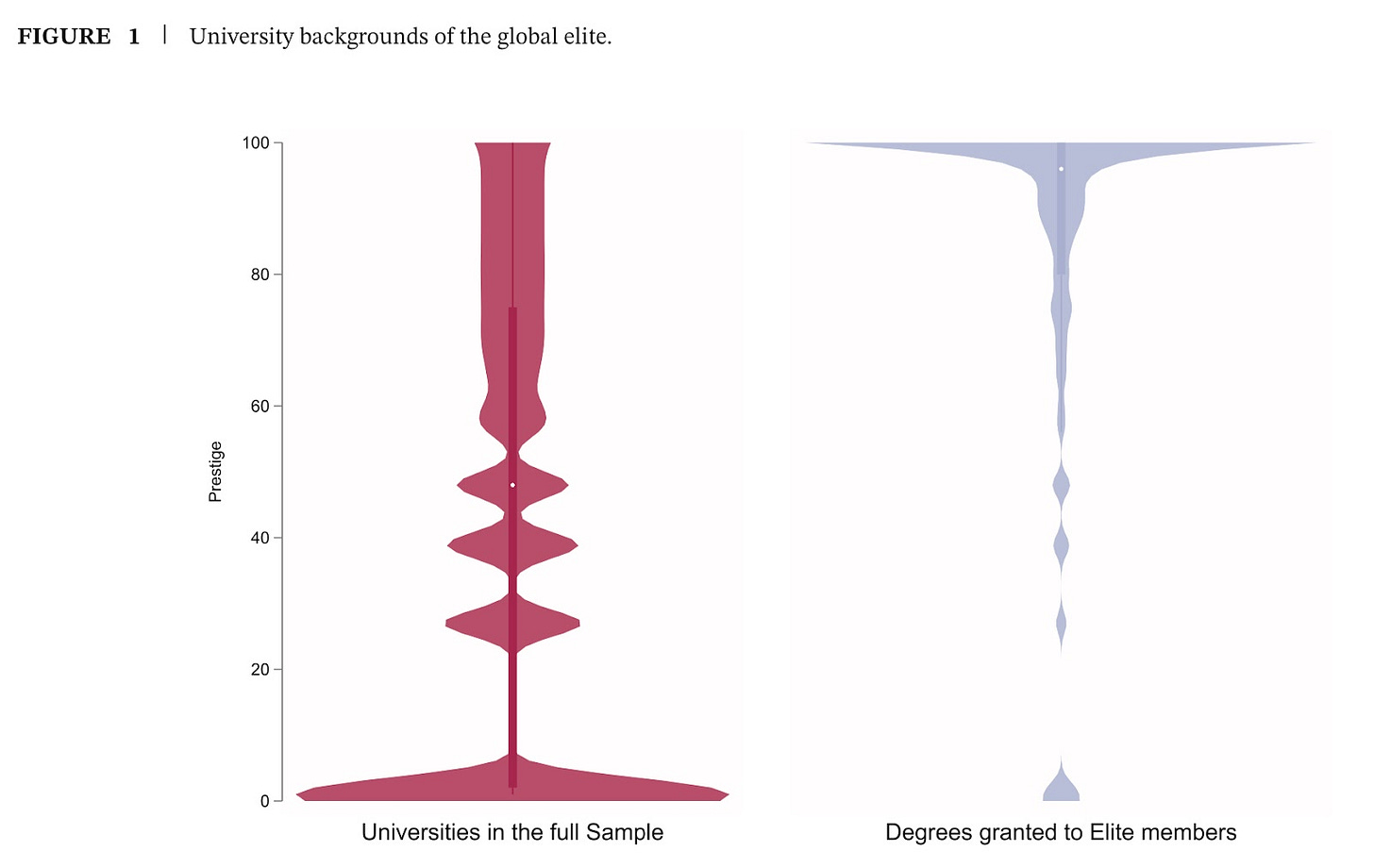

A recent paper by Ricardo Salas-Diaz and Kevin L. Young called “Where Did the Global Elite Go to School? Hierarchy, Harvard, Home and Hegemony” (2024) reveals that a staggering percentage of both American and Global Elites are educated at Harvard or other Ivies. While different definitions of elite exist, and you can slice the data many ways, it is pretty clear that Harvard, along with other top US and UK schools, is the linchpin of elite networks, even at a global level. These authors defined elites by looking at wealth (billionaire lists) and power (heads of state, central bankers) and influence (heads of NGOs and multilateral organizations). Notably, this list did not include celebrities or musicians, which in the age of social media seems like an omission to me. But overall the idea makes sense.

Note that even among non-Americans, who are much less likely to go to US schools, Harvard still comes out on top. Also note how the chart above had to be extended to account for the enormous amount of US nationals in Global Elite who went to Harvard.

A skeptic could say, ‘Harvard doesn’t make elites, the children of elites choose to go to Harvard’. And the authors note this is probably partially true. But the fact that many elite students go to Harvard only increases the value of the degree, and the network. So it’s probably a self-reinforcing effect where Harvard both benefits from elite attendance while also creating new elites. Considering truly elite children can go to almost any school, it is notable that so many of them want to go to the Ivies + Oxbridge, etc., suggesting the school network does matter to reinforce their elite status.

This chart demonstrates how overrepresented top university education is among global elites, but also somewhat hopefully demonstrates that at least a small amount of meritocracy appears to exist, with some elites being minted despite low prestige educational backgrounds. (Or viewed with a negative lens, perhaps the low-achieving children of elites still become elite, despite failing in school.)

This study makes the GPA inflation totally logical, if you consider the purpose of Harvard to be an elite networking institution with a great school attached, instead of as a great school that happens to be good for networking. One could surmise the deal is thus: Why anger future donors to your endowment with low grades, when you can mostly make students (who are disproportionally likely to be rich and powerful in the future) look and feel good?

This self-reinforcing nature of elite networks - whether in universities, cities, or industries - creates ripple effects throughout society. These second-order effects of our increasingly network-stratified society deserve closer examination, as they help explain everything from marriage patterns to geographic mobility to political polarization.

Second order effects?

Here is a mix of speculation and research about second order effects from our increasingly network-stratified society.

If poorer people increasingly cannot afford to move to big cities, and elites sort themselves into top universities, what does this say about inter-class marriages, and the children of the marriages (or relationships) which do occur?

First, and most obviously, if you are a poor person who never leaves the deep south, you will probably never meet the partner, let alone the friends, you would have met in a big city. Physical proximity has long mattered for relationships. Given that romance essentially always has a physical dimension, and friendship usually does, this makes intuitive sense. This 1932 study found that lots of people (surprise!) marry people relatively close in physical proximity to them, and the farther away someone lives from them (pre marriage) the rarer such a pairing is. This 1950 study found that people disproportionally became friends with those closest to them. This 2021 study found that being seated next to someone increases the odds of a friendship forming. Even in the era of online dating, almost nobody is using apps to date someone five states away.

These friendships and relationships really matter, especially for children. Raj Chetty et al.'s 2022 paper on social mobility bluntly notes in the abstract "If children with low-SES parents were to grow up in counties with economic connectedness comparable to that of the average child with high-SES parents, their incomes in adulthood would increase by 20% on average." This finding is staggering - simply being around more economically connected people dramatically improves life outcomes. And if poor people, like my grandfather, can no longer move to big cities for a better life, society becomes less dynamic and certain people may get economically stuck. While technological advances and remote work might seem like solutions, they may actually be making in-person networks more valuable by making them more exclusive.

This economic sorting has profound social and political implications. With increased sorting by economic opportunity, it should be no surprise that polarization increases. And in an era of increased sorting and political polarization, people will increasingly marry those who are politically similar to themselves. The data back this up: In 1973, only 53% of newlyweds agreed politically, but by 2014 this figure was 74%. This, in turn, probably only increases polarization, creating a feedback loop of social separation.

This data on the increasing percent of wealth held by the richest individuals demonstrates the importance and resilience of the network power of wealthy individuals.

But on a global scale, the network effects seem to be even stronger. The Financial Times, as well as Twitter/X is filled with posts and threads of Europe's relative decline when compared to the United States. Why is this? The US benefits from a large population, with a single market, a homogenous language and culture, essentially the same legal system across states, the world's reserve currency and more. These aren't just economic advantages - they're network advantages that compound over time.

By contrast, academics continue to argue that the Eurozone is not an optimum currency area. That is, the Euro itself exists for political reasons to bridge gaps between countries, rather than for pure economic ones. A diversity of traditions and laws and languages and cultures—which is sociologically and culturally a benefit—is economically a disadvantage, as a Spaniard moving to Germany is actually moving to an entirely different linguistic and cultural space, while an Alabaman moving to Chicago is simply making their winter (much) colder. Add on top of that a less entrepreneurially friendly culture, and harsher regulations (particularly around bankruptcy) and you have a recipe for underperformance.

This network effect is particularly visible in venture capital. A 2013 study suggests venture capital firms are more likely to invest in firms closer in proximity to themselves, and given the continued importance of Silicon Valley, this has probably only intensified. The concentration of capital in specific geographic areas creates a self-reinforcing cycle: talent goes where the money is, and money goes where the talent is. This fact also contributes to a brain drain from Europe to the United States, which is also compounded by the fact that US-listed firms trade at higher multiples than EU listed ones, which has led some EU firms to relist in the US.

Whether you're trying to be a folksinger or a longshoreman, or even a janitor, high housing costs lead to a diversity of problems, making it harder to join elite networks. And as the study on Harvard and global elites shows, these networks are real, are powerful, and are self-reinforcing. When we understand the Raj Chetty et al. 2022 results that merely growing up in more networked places increases lifetime income substantially, it suddenly becomes clear why parents fight so hard to get into the "right" schools, neighborhoods, or social clubs. Indeed, thinking in terms of networks makes expensive country clubs less of a consumption good and more of a human capital advancement good. Networks matter - not just for individual success, but for the very fabric of our society.

But where do we go from here? This is not just a story about housing costs or elite universities - it's about how opportunity itself is becoming concentrated and self-reinforcing. While technological advances like AI learning tools may democratize education, allowing motivated students anywhere to academically excel, this may paradoxically make elite social networks even more valuable. When anyone can learn anything online, the scarcest resource becomes the in-person connections that can't be digitized.

The solutions are both simple and difficult. Simple because we know what works: abundant housing in productive cities, expanded university access, and infrastructure that enables people to physically access networks of opportunity. Difficult because these solutions require overcoming entrenched interests that benefit from artificial scarcity. Because the poorest among us are hit hardest, the cost of inaction is hidden from view, but that cost is growing every year.

From Bob Dylan finding his voice in Greenwich Village, to my grandfather finding opportunity as a longshoreman in Brooklyn, to Tim Cook getting his first break through an IBM recruiter at Auburn - these stories remind us that networks aren't just about individual success but about society's ability to find and nurture talent wherever it exists. Networks will always matter; the question is whether we make them ladders of opportunity or walls of exclusion.

____

As you already know, this is The Studies Show and my name is Alexander Webb and I’m proud to say I just finished my PhD, which was on trust in financial networks and transactions. Thank you all for reading!

Please feel free to comment if you have any stories or papers to discuss.

While there is controversy over Hsieh and Moretti’s results, with one replication saying the true figure is 0.02%, other academic studies (Duranton and Puga (2020), Duranton and Puga (2023, and the already cited Ganong and Shoag paper) seem to confirm it is directionally correct, and some believe the Hsieh and Moretti study dramatically underestimates their own findings. As someone who briefly lived in Silicon Valley after living in Hong Kong, and was amazed at the lack of density in the world’s technological hub, Hsieh and Moretti’s results certainly feel very true, and I am sure academics will continue to study this important issue.

This was really incredible Alexander! I'm a huge Bob Dylan fan, and I love reading and writing about housing. I'd never really thought about network effects to this extent. I guess in my head success seems so social media driven right now, that you forget about the boots-on-the-ground growing. Going to give this a re-read. Great stuff!

Congrats on finishing your doctorate. Great post.

The self-reinforcing aspect of elite institutions is interesting to me. I just wrote a post about consulting and finance's relationship with elite colleges; colleges want wealthy and high prestige graduates and so are more than happy to provide finance shops and consultancies premium access to their students. Since so many elite students end up in these industries, they are perceived as high-status and the feedback loop repeats.