Venezuela and the Cynical Lessons of Iraq

Compellence and Trump's capture of Maduro

Recent US action in Venezuela suggests that the Trump administration has learned extremely cynical, but strategically coherent, lessons from US failure in Iraq. Whether you find that reassuring or terrifying depends on what you think American foreign policy is for.

In Iraq, the US invaded a dictatorship, occupied the country for years, dissolved the military, purged the bureaucracy, and tried to build a democracy from scratch. An insurgency followed. Hundreds of thousands died. Trillions were spent. It is largely viewed by the American public as a failure.

The political scientist Alexander Downes has spent years studying what happens after foreign-imposed regime change. His findings are bleak: regime change increases the likelihood of civil war, violent removal of the newly installed leader, and continued conflict between the intervening state and its target. The Iraq model—maximalist intervention, institutional destruction, attempted democratization—is probably the approach most likely to produce chaos.

Trump’s Venezuela operation looks like an attempt to avoid Iraq’s biggest mistakes. The U.S. carried out strikes on targets in and around Caracas, captured Maduro, flew him to New York — and, at least for now, did not occupy the country. Venezuela’s state apparatus remains intact: the military wasn’t dissolved, the bureaucracy wasn’t purged, and Delcy Rodríguez has assumed interim power.

This isn’t true regime change. It’s closer to compellence.

The term comes from Thomas Schelling, the Nobel Prize-winning economist who wrote Arms and Influence in 1966. Schelling distinguished between deterrence—threatening someone to prevent them from acting—and compellence—threatening someone to make them act. Deterrence is somewhat passive: you draw a line and wait. Compellence is active: you apply pressure until the other side does what you want.

Trump demonstrated he wasn’t bluffing by conducting one of the most dramatic extractions of a head of state in modern history. Now the message to Venezuela’s remaining leadership is simple: cooperate, and everyone makes money. Resist, and you’re next.

In this case, Trump’s deal appears simple: Adopt a relatively pro-US foreign policy, and invite US oil companies back into the country.

Todd Sechser’s analysis of over 200 cases of compellence finds a 41.4% success rate, which is less than a coin flip, but almost certainly better odds than the US faced in Iraq.

Beyond looking at what Trump did, it’s important to notice what Trump didn’t do: He didn’t support the Venezuelan opposition. He didn’t call for free elections. He didn’t back María Corina Machado or Edmundo González, the leaders many Western governments consider the legitimate winners of Venezuela’s contested 2024 election. Instead, he’s signaling he’ll work with Delcy Rodríguez—Maduro’s handpicked vice president, now sworn in as interim leader—if she cooperates.

This is extremely cynical and disappointing from the perspective of American ideals. But on paper, the logic, however dark, is more coherent than Iraq ever was.

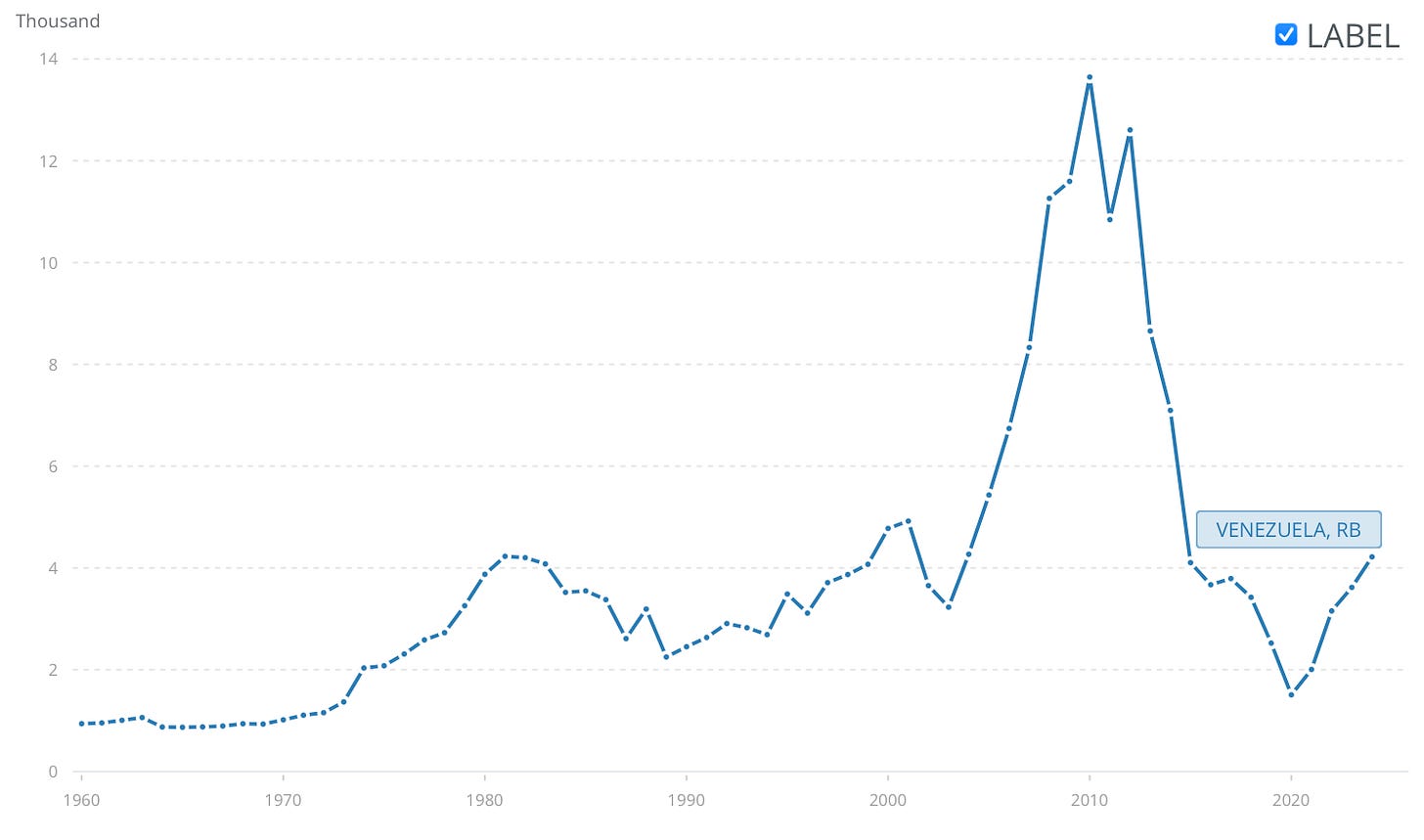

Venezuela seemingly has the largest proven oil reserves in the world. (Although some think these figures were fudged). Under Maduro, the economy collapsed from a GDP per capita of around $12,000 to roughly $4,000—a decline that began before US sanctions. The country is so poor now, but has so much potential wealth, that even a corrupt deal with the US could make ordinary Venezuelans materially better off. And it will certainly make cooperative elites richer. Trump is betting that these incentives are enough to make this arrangement work.

There’s another factor that may work in his favor. Iraq involved a majority Christian country occupying a majority Muslim one, which complicated the politics of legitimacy and fueled resistance. Venezuela is a Catholic country with its own history of democracy—Maduro, after all, just falsified an election rather than abolishing elections entirely. Whatever deal emerges won’t be as likely to be seen as a foreign system being imposed from outside.

Will it work? Honestly, we don’t know. Schelling himself acknowledged that compellence is harder than deterrence—you’re asking someone to actively change their behavior, which is psychologically and politically more demanding than asking them to refrain from acting.

There are real reasons to doubt the strategy. Rodríguez and the remaining leadership have spent years under sanctions and indictments. They watched what happened to Gaddafi and Noriega. They might calculate that cooperation merely delays their own eventual extraction—that the US will keep making demands once it sees weakness. The compellence literature suggests targets often resist even when capitulation seems rational, precisely because they don’t trust the coercer to stop.

And the minimalist model can become maximalist quickly. If Rodríguez faces internal opposition, if the military fragments, if the promised investment doesn’t materialize, Trump may face pressure to escalate. The absence of occupation today doesn’t guarantee its absence tomorrow.

Sechser, cited earlier, notes several reasons why compellence strategies invite resistance that deterrence may not, citing several papers in the process:

Posen (1996) argued that acceding to a compellent threat invites future predation, whereas capitulating to a deterrent threat does not. A third possibility is that compellent threats are more likely to offend a target’s sense of national honor: Art (2003: 362) asserts that “compellence more directly engages the passions of the target state than does deterrence because of the pain and humiliation inflicted upon it”. Behavioral psychology offers a fourth explanation, suggesting that individuals’ inherent aversion to losses may make them more resistant to compellent threats (Davis, 2000; Schaub, 2004).

But compared to invading with over 100,000 American troops, Trump’s actions are a low cost, and likely lower risk way to use American power. The real risk seems to be the continued erosion of international norms and laws, with the US action contributing to a “might makes right” paradigm. The long-term consequences for the international order likely outweigh whatever short-term gains the US extracts from Venezuelan oil.

Trump’s actions in Venezuela are cynical and dangerous. But Trump’s Venezuela strategy is more coherent than Iraq was. It avoids the most obvious errors of the post-9/11 era. It reflects a clear-eyed, transactional view of American interests. The lack of idealism is sad. But that doesn’t mean it won’t help Trump achieve his goals.

Yet coherent isn’t the same as wise in the long term, and avoiding Iraq’s mistakes doesn’t mean this will succeed.

We are in a new era. It is clear the US has learned important lessons from Iraq.

What lessons Venezuela has to teach America remains to be seen.

The Studies Show was founded by Alexander Webb, PhD, in early 2023. Alexander Webb has also written for The New York Times, National Geographic, WIRED, Business Insider, and other publications, in addition to co-authoring multiple peer-reviewed academic papers.

More from The Studies Show: